He was dismissed on day two of a new job. The reason: Choices he made 33 years earlier

3:17

Ex-prisoners call for Clean Slate Act reform

VIDEO CREDIT: Stuff

A criminal record can shadow someone for life, limiting jobs, housing, and access to insurance, even decades after they last broke the law. One expert calls it a “never-ending punishment” that begins at the gate. Reform, they say, would not only be simple, but bring New Zealand more in line with the rest of the world. Phoebe Utteridge investigates.

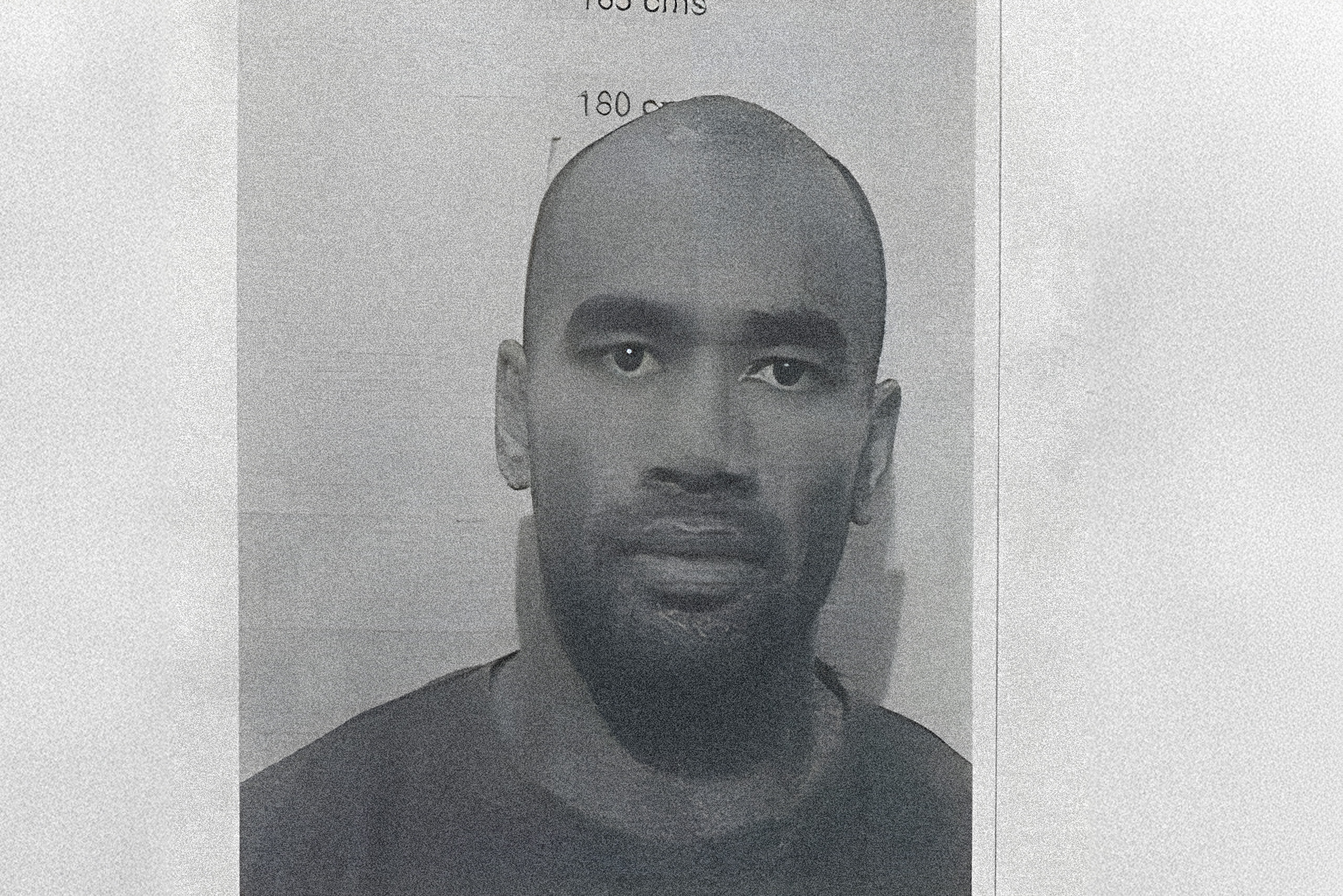

Richard

Richard quit his job when he landed a new position as a sales representative in October.

His employment contract was signed, he started building relationships with his co-workers and completed his first shift.

That night, he drove home in the company ute.

https://buy-au.piano.io/checkout/template/cacheableShow.html?aid=hJGmGBJdpa&templateId=OTRNR2USMG1F&offerId=fakeOfferId&experienceId=EXFE0UYBLK0G&iframeId=offer_2d53741f4a3014ac49b5-0&displayMode=inline&pianoIdUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fid-au.piano.io%2Fid%2F&widget=template&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.stuff.co.nz%2Fnz-news%2F360879114%2Fhe-was-dismissed-day-two-new-job-reason-choices-he-made-33-years-earlier

But early the next day, he was called into a meeting, stood down immediately and sent home in a taxi.

The reason?

His voluntary criminal record check had only just landed in the hiring manager’s inbox, and despite decades having passed since he last broke the law, he was let go.

Shocked and angry, Richard was left at home, without a job to go to and shrouded in shame.

Read More

NZ NewsMum and child fled as landlord drove digger into their homeWorld NewsMountain lion roams posh San Francisco neighborhood before being capturedpoliticsJudith Collins retiring from politics, has new job locked in

“I paid for my crimes over 30 years ago, but this week I paid again,” Richard says.

The 53-year-old’s criminal record, seen by Stuff, shows his last prison sentence was 33 years ago in 1992, when he was 20. His offences ranged from possession of a cannabis pipe to burglary, arson and unlawfully having a firearm.

In 2002, he was convicted for driving drunk and carelessly. From that point on, his record is clean.

Inside the tidy, sun-filled home he shares with his wife and youngest son, Richard tells the story of how he grew up in institutions, under the care of the state, and was moved from place to place all across the country.

He says he got in with the wrong people, and made bad choices. He regrets them now, but he also acknowledges his experiences shaped him into the person he is today, and he doesn’t want to hide from his past.

“I didn’t have much of a chance,” he says. “But it was after I got out of prison that I decided it was time to be responsible for myself, and that’s why there’s been nothing since.”

I paid for my crimes over thirty years ago, but this week I paid again.Richard

In prison, Richard says he took every opportunity to better himself. He “read the library out of books”, completed his school certificate and checked himself into a rehabilitation programme upon his release.

For him, he says, the prison system did what it is supposed to do – it corrected his course.

After his release, Richard went on to work in a number of different jobs, from making mattresses, to sales, to being an auto electrician.

Contact the reporter: phoebe.utteridge@stuffdigital.co.nz

But still, today, he says he is paying the price for what he did all those years ago.

Soon after he was let go, Richard was offered another job. He gave that employer a copy of the same criminal record, apprehensive about his response.

“He just said, ‘That was in 1992, I don’t give a stuff’.” He says the new job is going well.

Richard only wants his first name used, to protect his new employment.

Sarah

Sarah* doesn’t know when she’ll be asked to work a shift packing orders in a warehouse until 3am.

Sometimes she gets the call up a few hours beforehand, other times she gets about a day’s notice. The work is monotonous, and unreliable.

But Sarah takes what she can get.

Despite being skilled, having experience in business management and administration, and submitting countless applications, no one will give her a full-time job, not even in a supermarket.

In 2005, aged 25, Sarah was convicted of one charge of importing a Class A drug and another of cultivating cannabis. She was sent to prison for three and a half years.

Sarah says she was grappling with an abusive childhood and her mental health at the time. She turned to drugs to cope, “suppressing everything”.

She entered into a relationship with a much older man, and spiralled further into addiction.

It all came to a head, Sarah says, after she and her partner visited Australia, where he was from. There, she says she picked up a bag of methamphetamine and flew back to New Zealand.

“When you’re on methamphetamine, you think you can get away with anything and you’re invincible,” she says.

I work harder, strive to do more and hold more integrity because of my past.Sarah

That, of course, was not the case. Back in New Zealand, Sarah was arrested at the airport and sent straight to prison. Police searched her and her partner’s house, where they found cannabis plants.

She points to a 2020 case in which a Christchurch woman was sentenced to 11 months’ home detention for attempting to import methamphetamine, cultivating cannabis and possessing other drugs for supply.

Sarah says back then things were different and the judge had made an example of her, and the three and a half year sentence was harsh.

She served her time, and although she’s not proud of what she did, she says she doesn’t regret it.

“Because if I didn’t go into jail and have that time to get clean, I wouldn’t be alive today.”

For Sarah, the support she received in prison was a turning point. After she was released, she went to a rehabilitation centre and says she hasn’t touched drugs since.

But much harder than her time in prison, Sarah says, have been the years since she was released, always being judged for her past, constantly having to prove herself.

“I work harder, strive to do more and hold more integrity because of my past,” she says.

Sarah’s criminal record, provided to Stuff, shows she hasn’t had any convictions since her drug charges in 2005. “I haven’t even got any demerit points,” she says.

But, still, what she did that day 20 years ago, stops her from getting a job.

“I applied for six supermarket jobs and they won’t even answer me back. Crickets,” she says.

Permanent records a ‘never ending punishment’

The Criminal Records (Clean Slate) Act was brought into law by the fifth Labour government in 2004.

First introducing the bill in 2001, then-Justice Minister Phil Goff said “people with minor convictions who are no longer offenders should be able to leave their past behind them.

“There comes a point in time where minor convictions are no longer of any public concern and people should be freed from the stigma of that offending and the fear of having it revealed.”

The scheme allows a person to conceal their criminal record if they have gone seven years without a conviction. (Excluding cases involving a select number of offences, mostly sexual).

But, it’s off the cards if that person has done prison time.

And that’s that. It’s black and white.

It is that aspect of the law that is not working, Associate professor of law Dr James Mehigan says from his office at the University of Canterbury.

It is, he says, a “never ending punishment” and one that is not factored into sentencing.

“I’d like to see prison sentences included. It’s far too small a scope.”

And changing that, Mehigan says, would be simple.

Practically, police databases would just need to be adjusted to new thresholds, he says. “People with convictions can then apply for jobs they otherwise couldn’t.”

In 2023, Labour MP Duncan Webb introduced a members bill to expand the eligibility criteria for the Act, allowing people who had served prison time of up to one year to get a clean slate if they had gone 10 years without reoffending. It made it to its second reading in Parliament, but didn’t make it into law.

Goff, the architect of the Act, says his team was conservative in their approach back in the early 2000s, given the proposal was relatively controversial at the time.

He says it is due for a review. “Twenty years is a long period of time.

“It behoves parliamentarians to look at past legislation and say ‘Is this still fit for purpose? Does it need amendment? Has it caused problems that would make us cautious about liberalizing it, or has it caused more problems because it still leaves a lot of people out who are living in the past and should have the right to move on.”

Justice Minister Paul Goldsmith says although he cannot comment on specific cases, he is receiving advice on the Act “more generally.”

He says he is aware of the concerns raised and “may consider potential reforms when resourcing allows”.

“We currently have an extremely busy legislative agenda, particularly in the justice space.

“The Government recognises the importance of rehabilitation, and is investing $78 million to extend rehabilitation programmes to the 40% of prisoners who are on remand.”

New Zealand a ‘cruel’ country in international context

According to Ministry of Justice data, the number of people who received a prison sentence increased by 14% in the year to June 2025.

Richard has a message for the Justice Minister, and the Government more broadly.

“You brought me up. You’ve been my mum and dad and you released me into the world after training me.”

Richard says most of the things he did that landed him in prison, he learnt while he was in state care.

“I’ve broken the mould that you created, and gone my own way. And I think it’s time that you gave me a break.

“A fair go,” he says, looking down at his feet and sighing. “That’s all I want, a fair go.”

Sarah says people are often shocked when they hear she has a criminal history. She does not fit the stereotype that springs to their minds.

She says they always ask, ‘Can’t you just get it clean slated?’. She’s had to explain why she can’t over and over again.

“The whole system is broken in that way,” she says. “They expect people to rehabilitate, but then they’re still punished for a lifetime.

“I want people in policy to see how damaging that is.”

Australia, the United Kingdom, and even California include prison sentences in their legislation equivalent to the Clean Slate Act, Mehigan says.

“By international standards, New Zealand is a cruel country.”

Everyone Stuff spoke to for this story agreed there are crimes that should always be declared, such as sexual harm, offending against children and extreme violence.

“But there are many people who go to prison for things in the past which don’t indicate they are a risk to society, an employer or an employer’s clients,” Mehigan says.

“Many jobs involve no working with the public, let alone children or vulnerable people and ex-prisoners are often suitable for those roles with a little bit of training.”

1:25

Robert Purchase has applied for almost 8000 jobs

VIDEO CREDIT: Stuff

‘Maybe I’m better off inside’

Stuff reported 48-year-old Robert Purchase’s desperate plight to find work in October.

The struggling beneficiary says he has been rejected for almost 8000 roles because of a prison stint from 28 years ago. His crimes ranged from shoplifting to unlawfully carrying a weapon and assault.

Purchase served his time and says he has not committed a crime since – a claim supported by a copy of his criminal record he supplied Stuff.

Scrolling through rejection letter after rejection letter, he says he fleetingly thought about returning to criminal activity to get money over the years. But that wasn’t what he wanted, all he wanted to do was work.

Lawyer Jamie Martin, committee member of prison reform organisation Howard League, says that sentiment is common among prisoners, who lose faith in being able to successfully reintegrate into the community and live crime-free lives.

“I can relate to why they would find that really discouraging, and why they think ‘well, maybe I’m better off inside’,” he says.

It’s not an easy time to be looking for a job, even without a criminal history attached to your name.

On Wednesday it was announced unemployment was at its highest since September 1994, with 160,000 people without work in the September quarter of 2025.

That’s about 12,000 more people than the same time period in 2024.

After sharing his story, Purchase finally found work in traffic management. He still wants change for others in his position, who build better lives for themselves and want to contribute to society.

The right to a second chance

“Prisoners do deserve a second chance,” Mehigan says.

“It’s called the Department of Corrections because we as a society have decided that people who go to prison or who are punished are going to do so to be corrected, but if they come out and they have no chance of getting a job or stable housing, then that process of correcting is almost completely undermined.

“So by disadvantaging people through the attachment of a criminal record many years after they’ve gone clean, you are making their lives much more difficult than they need to be, and ultimately making society less safe.”

It’s hard to imagine a more drastic turnaround than the life of Mark Talanoa.

Speaking with Stuff from his family home in the small rural settlement of Tuahiwi, there is little pointing to the 36-year-old’s past.

Talanoa is a builder, dedicates most of his time to charity work and breeds ducks on a lifestyle block he shares with his wife Desiree and two young daughters Bella and Nariah.

He’s also a 501 returnee, spent much of his younger years dealing and using drugs, and was eventually sent to prison for setting fire to a gang headquarters, and firing shots at a gang president’s house and trying to blow up his car.

Talanoa was once a talented sportsman, living in Australia playing rugby league on a scholarship.

He buckled under the pressure, became injured and gave up. That was when he turned to drugs, and fell out with a gang.

He served his time, and was deported to New Zealand in 2017. Upon their return, he and Desiree tried to make a life for themselves in Christchurch, but Talanoa says every time he applied for a job, a background check revealed his history and he was knocked back.

“It was so hard to find work,” he says.

But, he persisted. Eventually, Talanoa got temporary work as a labourer for a Christchurch construction company.

After a year of sweeping floors, picking up rubbish and lugging timber, his reliability and hard work was rewarded with a full-time job.

Mark Talanoa turned his life around after serving prison time in Australia and being deported back to New Zealand.

Now, Talanoa teaches rangatahi to build for a kaupapa Māori organisation, Noaia, and runs Road II Redemption charitable trust alongside Desiree, supporting people in the justice system, or at risk of entering it.

Talanoa says he is in the position he is today because people believed in him. “But it’s tough,” he says, his voice wavering.

He wasn’t expecting the tears. “I rarely get emotional.

“I’m one of the lucky ones who has turned my life around with all the support that I’ve had. But that’s not the same for everyone,” he says.

He believes everyone deserves a second chance.

“If we don’t give our men and women the opportunity, how do we expect them to change? We just keep putting them back into this revolving sort of door and nothing good comes from that.”

He says the system is set up to fail. “It doesn’t want change. It doesn’t want people to rehabilitate.”

Whilst addicted to drugs Adrian Pritchard, 54, carried out “hundreds” of burglaries, seeing him dubbed “New Zealand’s most wanted criminal”.

But after 10 years in prison, Pritchard worked to become sober and is now a community support worker in Hawkes Bay Regional Prison, living a quiet life with his wife of 10 years and three daughters in Hastings.

He wrote a book called 2nd Chance, detailing finding his way out of a life of crime. “We aren’t born bad,” he says.

The ex-prisoner says permanent records keep people like him in a “crime mindset” and stops them from moving forward with their lives.

He’s had trouble finding paid work over the years, and now spends his time trying to help others in a similar boat. “You don’t even get a look in.”

He says prison has a revolving door, a failure in the system he puts down to the limitations of the Clean Slate Act.

His question for those in power?

“Why are you guys building more prisons instead of trying to help people reintegrate into society where we can become more profitable and better for the community?”

Sarah acknowledges she made a “huge” mistake, but she feels she will be punished for it forever.

“I took responsibility, served my time, rebuilt my life, and established a track record of reliability, professionalism, and community contribution.

“Yet that is still not enough.”

The now-45-year-old is articulate, and well-spoken. She follows politics and the news closely.

She also desperately wanted to use her real name for this story, and toyed with doing so for some time.

But, she says, she knows what sort of backlash can come from others knowing her history, and she so needs a job. So, she keeps “trucking on”.

But it is exhausting, she says with a sigh, her eyes brimming with tears.

“I’m not asking for handouts. I’m asking for a fair chance.”

*Not the subject’s real name.

‘They’ve always been scapegoats’: Behind Australia’s crackdown on youth crime

Are states like Queensland and Victoria really facing a youth crime “crisis”? Here’s what criminologists, political experts and Indigenous advocates say.

Published 6 April 2025 6:31am

By Emma Brancatisano

Source: SBS News

Image: Youth crime has dominated recent debate in Australia, particularly in Victoria. (SBS News)

This week, First Nations human rights leaders filed a complaint with the United Nations (UN) over Australia’s youth justice policies, calling them “draconian” and “discriminatory”.

The move was backed by the Human Rights Law Centre and argued that laws in place across Australian states and territories are perpetuating the “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment of children” by legal systems, noting in particular the use of spit hoods, solitary confinement and strip searching.

The complaint, which was lodged with the UN’s Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, follows an escalation of ‘tough-on-crime’ rhetoric over recent months by some Australian politicians and media commentators, labelling youth crime a “crisis”.

READ MORE

On life and liberty: human rights leaders take concerns about youth justice to United Nations

In Victoria in particular, the issue has dominated recent debate in reporting from parts of the media and in parliament, even prompting a petition led by FM radio hosts calling for bail reform for repeat offenders.

“Our state is facing a crime crisis that has never happened anywhere in this country at this level,” the state’s Opposition leader, Brad Battin, said in a grievance debate in parliament in February.

“We read about it in the news each and every day. We see it on our streets. We see it in the fear and hear it in the voices of those that have been let down by our broken justice system.”

Youth crime is out of control.

In a marathon sitting last month, Victoria’s parliament passed what Premier Jacinta Allan called the “toughest” bail laws in the country, “putting community safety first”.

The legislation mirrors changes that have come into effect in Queensland and the Northern Territory in the past year, which some have described as punitive.

This week, the Queensland government announced a further 20 juvenile offences to be introduced under its “adult crime, adult time” laws.

But criminologists and legal and human rights experts argue such changes lack scrutiny, won’t work to prevent crime and will disproportionately impact First Nations communities.

Others have questioned whether the crackdown on youth crime is proportionate or being weaponised for political gain.

LISTEN TO

‘It burns a hole in my heart’: UN hears Australia’s breaching obligations to First Nations children

SBS News

07:32English

For Gunggari person Maggie Munn, director of the First Nations Justice team at the Human Rights Law Centre, it feels personal.

“As an Aboriginal person, I know firsthand what laws like this do to our communities, the increased resourcing that goes to police as a result of laws like this, the punitive nature of law and policy that is weaponised against Aboriginal people,” Munn tells SBS News.

Youth crime rates: what do the figures say?

Renee Zahnow is an associate professor in criminology at The University of Queensland. She says, historically, young people have been at the centre of many “moral panics”.

But broadly speaking, they are responsible for a “small amount” of crime when compared to adults.

“What we’ve seen generally over the years is that crime among young people, like all crime, has been declining,” she says.

“We had a major decline when COVID-19 hit … and what we saw afterwards was an uptick as we returned back to the normal trend [pre-COVID levels].”

According to the latest recorded crime statistics from the Australian Bureau of Statistics in March, there were 340,681 offenders proceeded against by police across the country in 2023-24 — a 2 per cent decrease from the previous year and the lowest number since the collection series started in 2008-09.

Youth offender rates per 100,000 persons aged between 10 and 17 years from 2008 to 2024. Source: SBS News / Australian Bureau of Statistics

Of these offenders, 46,798 (or 14 per cent) were aged between 10 and 17 years old — a decrease of 3 per cent from the previous year.

Accounting for population change, the youth offender rate dropped from 1,847 to 1,764 offenders per 100,000 people in that age bracket.

Over two-thirds of youth offenders were male, and the most common age was 16 years. Those aged 14-17 made up around 82 per cent of youth offenders.

Zahnow says the recent focus on youth crime in Australia is inconsistent with offending rates, which are declining overall.

“A lot of the time, youth become a focus, and we use this sort of language to talk about them because when we think about the groups in the community that actually can influence what’s in the media, what’s being said publicly, and who can vote, it’s not youth,” she says.