Should police be able to interrogate kids alone? A growing number of states say no

The Legal Rights Center in Minneapolis holds trainings to teach young people how to assert their rights in police custody.

Jaida Grey Eagle for NPR

Most people have heard a version on TV of what are known as the Miranda Rights: “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you.”

It’s another thing entirely to hear them in person when a police officer is reciting them while placing you in custody.

“These guys have the power to lock you up. They got guns on their hip. It’s intimidating,” a 22-year-old recently told NPR. We aren’t publishing his name because he’s on probation and worried he might face retaliation for talking to a reporter.

The first time he heard those words, he was in the sixth grade. Police were arresting him for threatening a bully with a pocket knife.

“They didn’t call my mom. They didn’t call a lawyer. They told me my rights, but I’m 12. So I didn’t fully understand what was happening,” says the young man.

That day, he didn’t ask for a lawyer, and he did talk. Studies show nearly all juveniles make the same choice: As many as 90 percent waive their Miranda rights. Yet legal experts say children and teenagers don’t understand the consequences of doing so.

Now, some states are working to fix that. In the last three years, at least four states — including California, Maryland, New Jersey and Washington — have passed laws banning police from interrogating children until that child has spoken to a lawyer. Illinois has introduced a bill broadening its protections for juveniles questioned by police, and other states – including New York and Minnesota – have introduced similar bills.

‘They literally don’t have the same resources that fully grown people do’

The brain areas that govern impulsivity, self-regulation and decision-making aren’t fully developed until about the mid-twenties, says Hayley Cleary, an associate professor of criminal justice at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“It is fundamentally unfair to interrogate them in the same way we do adults when they literally don’t have the same resources that fully grown people do,” she says.

In a room alone with police, children and teenagers are more likely than adults to falsely confess to a crime. They’re also more vulnerable to incriminating themselves or pleading guilty when a lawyer wouldn’t have advised it, says Marsha Levick, chief legal officer of the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia.

That can lead to harsher punishment, like more time in juvenile detention. Being incarcerated disrupts childhood. Kids who experience it are less likely to graduate from high school and more likely to be incarcerated as adults.

“Children plead guilty in juvenile court every day, and they’re represented by lawyers who are advising them and talking through with them what the consequences of that means,” Levick says. “To do it on their own with no one to explain to them what the right is that they’re giving up and what the consequences of giving up that right are, is simply unreasonable.”

After police questioned the now 22-year-old that NPR interviewed, he was put on probation. That started a cycle: He went to juvenile detention the next year at 13, and has been on probation or behind bars on and off ever since.

“At this point, it’s a part of my life, you know what I mean? As sad as it is to say. I don’t want to be in the system and have to deal with that for the rest of my life,” he says.

Chelsea Schmitz-Gillam, a juvenile defense attorney at the Legal Rights Center in Minneapolis, says there is an imbalance of power between young people and police during questioning.

Jaida Grey Eagle for NPR

Eventually, he connected with the nonprofit Legal Rights Center in Minneapolis. Chelsea Schmitz-Gillam, a juvenile defense attorney there, has represented him multiple times.

“He knows how to assert his rights when I am sitting next to him. We’ve practiced it many times,” she says. “I am also not a police officer.”

She remembers watching a recording of the young man being questioned.

“He says, ‘I think this is the time where I’m supposed to call my lawyer. I think this is the time where I shouldn’t be saying anything else,'” Schmitz-Gillam says. “The police officers – who are trained in their field, which is interrogation tactics, which our youth are not trained in – continue to have a conversation with him: ‘Well, it’s up to you, if you really think you need a lawyer, but also if you talk with us right now, look, there’s ways that we can make this easier for you.'”

‘States have moved towards building the responsibility on the system’

In a classroom last spring in St. Paul., Minn., a group of high school students listened to a presentation about what to do in police interactions.

The training was held by the Legal Rights Center which, in addition to providing legal representation, conducts “know your rights” trainings for young people around the Twin Cities.

The trainer asked the group if they thought people under 18 have the right to ask for a parent when questioned by police. Several students nodded yes, but the answer was no. Some seemed concerned. One said it made her worry about her little brother.

“Currently the responsibility is on young people to assert those rights,” says Malaika Eban, executive director of the center. “But a lot of states have moved towards building the responsibility on the system.”

Malaika Eban, executive director of the Legal Rights Center in Minneapolis, says some states are moving toward putting the responsibility on adults to assert the rights of young people in police custody.

Jaida Grey Eagle for NPR

There has been pushback among law enforcement, says Dave Thompson, a consultant who trains investigators in interrogation techniques.

For instance, Thompson says, will there be enough lawyers to talk to all these kids, or will police have to wait hours before asking questions on what might be an urgent case?

“I think it’s just this nervousness, ‘If we add these safeguards, we’re not going to get any more information,’ says Thompson, but he added, “if we do it the right way, and everybody’s rights are protected, that should benefit justice as a whole.”

Eban, of the Legal Rights Center, says it’s not about young people getting off the hook for wrongdoing, but about whether they should be questioned alone by an adult with power.

“Nobody wants that for their own child,” she says. “If we can just have that breath of: ‘Okay, what would I want to have happen if my kid did something wrong or was accused of doing something wrong?'”

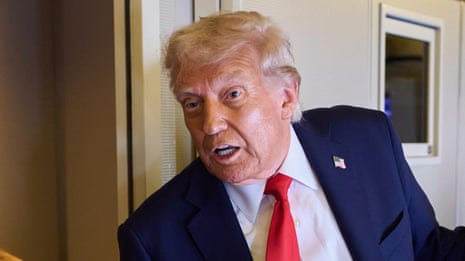

‘Censor-in-chief’: Trump-backed FCC chair at heart of Jimmy Kimmel storm

This article is more than 4 months old

Brendan Carr says he supports free speech – but has gone after broadcasters he deems are not operating in the ‘public interest’

Rachel LeingangThu 18 Sep 2025 21.32 BSTShare

“The FCC should promote freedom of speech,” Brendan Carr, now the chair of the Federal Communications Commission, wrote in his chapter on the agency in Project 2025, the conservative manifesto that detailed plans for a second Trump administration.

It’s a view he’s held for a long time. He wrote on X in 2023 that “free speech is the counterweight – it is the check on government control. That is why censorship is the authoritarian’s dream.”

And in 2019, in response to a Democratic commissioner saying the commission should regulate e-cigarette advertising, Carr wrote that the government should not seek to censor speech it does not like. “The FCC does not have a roving mandate to police speech in the name of the ‘public interest’,” he wrote on Twitter at the time.

But Carr has found himself at the center of the much-criticized decision by ABC to indefinitely cancel Jimmy Kimmel’s late-night show over comments the host made about Charlie Kirk’s killing. Despite the decision being, on its face, in opposition to free speech, Carr has used his position as chair of the commission, tasked with regulating communications networks, to go after broadcasters he deems are not operating in the “public interest”.

Before he was named chair, Carr said publicly that “broadcast licenses are not sacred cows” and that he would seek to hold companies accountable if they didn’t operate in the public interest, a vague guideline set forth in the Communications Act of 1934. He has advocated for the FCC to “take a fresh look” at what operating in the public interest means.

He knows the agency well: he was nominated by Trump to the commission in 2017 and was tapped by the president to be chair in January. He has also worked as an attorney at the agency and an adviser to then-commissioner Ajit Pai, who later became chair and appointed Carr as general counsel.

Tom Wheeler, a former FCC chair appointed by President Barack Obama, said Carr is “incredibly bright” and savvy about using the broad latitude given to the chairman, “exploiting the vagaries in the term ‘the public interest’”.

Instead of the deregulation Trump promised voters, the administration “delivered this kind of micromanagement”, Wheeler said.

“It’s not the appropriate job of the FCC chairman to become the censor-in-chief,” Wheeler said.

Since Kimmel’s suspension, Carr has said Kimmel’s comments were not jokes, but rather attempts to “directly mislead the American public about a significant fact”. During Monday’s show, Kimmel said that the “Maga gang” was “desperately trying to characterize this kid who murdered Charlie Kirk as anything other than one of them and with everything they can to score political points from it”. The comments came before charging documents alleged the shooter had left-leaning viewpoints.

Kimmel is just Carr’s latest target. As chair, he has used the agency’s formal investigatory power, and his own bully pulpit, to highlight supposed biases and extract concessions from media companies who fear backlash from the Trump administration if they don’t pre-emptively comply.

The commission itself hasn’t directly sought these actions from broadcasters. Carr has instead said publicly what the commission could do – for instance, signaling he would not approve mergers for any companies that had diversity policies in place – and companies have responded by doing what he wants. Nexstar, a CBS affiliate operator which first said it would not air Kimmel’s show on the local channels it owns, wants to buy Tegna.

Carr is honing a playbook, and so far it’s working. “It’s rinse and repeat,” Wheeler said. “I think we’ll continue to see it for as long as he can get away with it.”

Top Democrats on Thursday called for Carr’s resignation, and some suggested they would find a way to hold Carr accountable, either now or if they regain power in Congress.

The lone Democrat on the FCC, Anna Gomez, criticized Carr for “using the weight of government power to suppress lawful expression”. Gomez called ABC’s decision “a shameful show of cowardly corporate capitulation” that threatened the first amendment, and said the FCC was operating beyond its authority and outside the bounds of the constitution.

“If it were to take the unprecedented step of trying to revoke broadcast licenses, which are held by local stations rather than national networks, it would run headlong into the first amendment and fail in court on both the facts and the law,” Gomez wrote in a statement. “But even the threat to revoke a license is no small matter. It poses an existential risk to a broadcaster, which by definition cannot exist without its license. That makes billion-dollar companies with pending business before the agency all the more vulnerable to pressure to bend to the government’s ideological demands.”

Trump has cheered Carr as he collected wins against the president’s longtime foes in the media. On Wednesday, Trump called Kimmel’s suspension “Great News for America” and egged on NBC to fire Jimmy Fallon and Seth Meyers, their late-night hosts.

“Do it NBC!!!” Trump wrote on Truth Social.

Amid the criticism of Carr, Trump said the FCC chair was doing a great job and was a “great patriot”.

Breaking norms at the FCC

At the FCC, the chair has wide latitude and operates as a CEO of the agency, Wheeler said. There are four other commissioners, but the chair sets the agenda and approves every word of what ends up on an agenda, he said. The commissioners are by default in a reactive position to the power of the chair.

“What Chairman Carr has raised to a new art form is the ability to achieve results without a formal decision by the commission and to use the coercive powers of the chairman,” Wheeler said.

Without a formal decision by the commission, he said, there can’t be appeals or court reviews, one of the key ways outside groups have sought to hold the Trump administration accountable for its excesses.

The agency has historically been more hands-off about the idea of the “public interest”. On the FCC’s website, for instance, it notes that the agency has “long held that ‘the public interest is best served by permitting free expression of views’” and that instead of suppressing speech, it should “encourage responsive ‘counter-speech’ from others”.

In Trump’s first term, when Pai was chair, the president called for the agency to revoke broadcast licenses. At the time, Pai said, “the FCC does not have the authority to revoke a license of a broadcast station based on the content”.

Wheeler and a former FCC chair appointed by a Republican, Al Sikes, noted in an op-ed earlier this year that Trump had also used executive orders to undermine the independence of the FCC, instead making it into a “blatantly partisan tool” subject to White House approval rather than an independent regulator.

What Carr is trying to do

In an appearance on the conservative host Benny Johnson’s show that proved fateful for Kimmel, Carr alluded to ways the commission could take action against the late-night host. Carr carefully explained that he could be called upon to judge any claims against the broadcasters while also calling Kimmel’s comments “some of the sickest conduct possible.”

“But frankly, when you see stuff like this, I mean, look, we can do this the easy way or the hard way,” Carr said. “These companies can find ways to change conduct and take action, frankly, on Kimmel or, you know, there’s going to be additional work for the FCC ahead.”

The companies could handle it by issuing on-air apologies or suspending Kimmel, Carr said. He cited the idea of the “public interest” but also claimed there was a case that Kimmel was engaging in “news distortion”. In further comments to Johnson, he talked about the declining relevance of broadcast networks and credited Trump for “smash[ing] the facade”.

“We’re seeing a lot of consequences that are flowing from President Trump doing that,” Carr said. “Look, NPR has been defunded. PBS has been defunded. Colbert is retiring. Joy Reid is out at MSNBC. Terry Moran is gone and ABC is now admitting that they are biased. CBS has now made some commitments to us that they’re going to return to more fact-based journalism.

“I think you see some lashing out from people like Kimmel, who are frankly talentless and are looking for ways to get attention, but their grip on the narrative is slipping. That doesn’t mean that it’s still not important to hold the public interest standard.”