The Macabre Story Of Ed Gein, The Serial Killer Who Used Human Body Parts To Make Furniture

For years, Ed Gein holed up inside his dilapidated home in Plainfield, Wisconsin as he carefully skinned and dismembered his victims to fashion everything from a chair to a bodysuit.

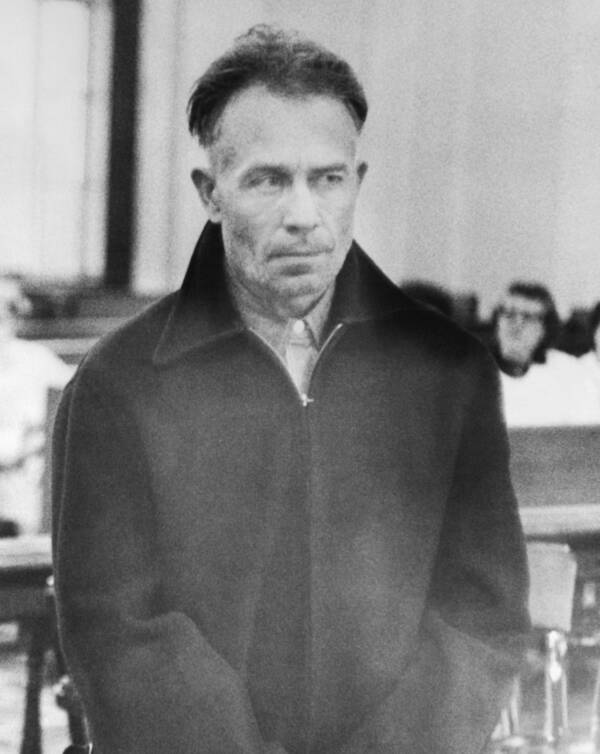

Bettmann/Getty ImagesAlso known as the “Butcher of Plainfield,” Ed Gein murdered two women and robbed untold graves in 1950s Wisconsin — then turned their skins into keepsakes.

Most people have seen classic horror films like Psycho (1960), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), and The Silence of the Lambs (1991). But what many may not know is that the terrifying villains in these three movies were all based on one real-life killer: Ed Gein, the “Butcher of Plainfield.”

When police entered his Plainfield, Wisconsin home in November 1957, following the disappearance of a local woman, they walked straight into a house of horrors. Not only did they find the woman they were looking for — dead, decapitated, and hung from her ankles — but they also found a number of shocking, grisly objects that Ed Gein had crafted using human body parts.

Police found skulls, human organs, and gruesome pieces of furniture like lampshades made of human faces and chairs upholstered with human skin. Gein’s goal, as he later explained to police, was to create a skin suit to quasi-resurrect his dead mother with whom he’d been obsessed for years.

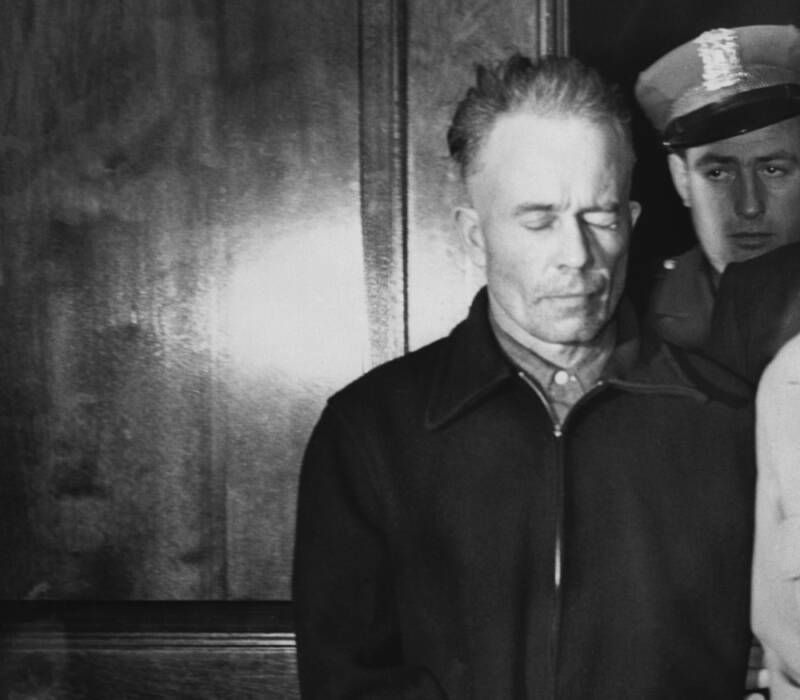

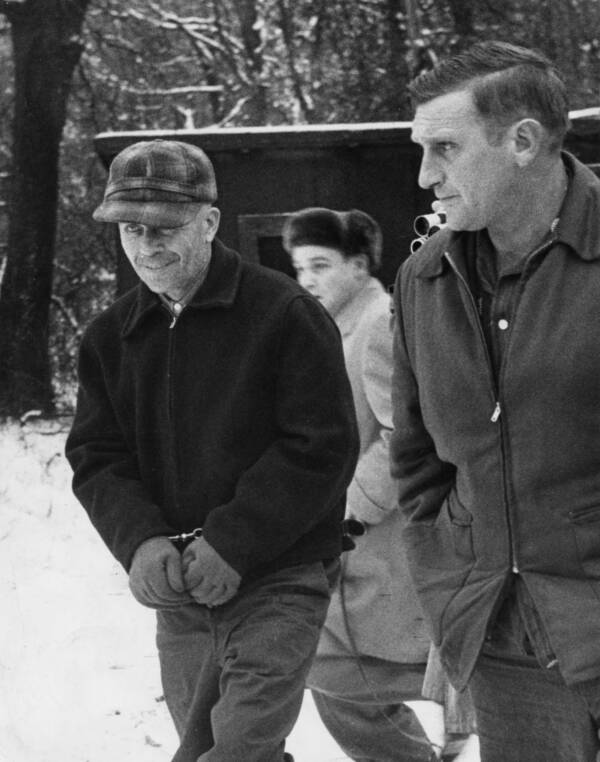

Bettmann/Getty ImagesEd Gein leading investigators around his property in Plainfield, Wisconsin.

This is the disturbing true story of Ed Gein, the murderer and grave-robber whose atrocities remain uniquely haunting to this day.

Ed Gein’s Early Life With His Overbearing Mother — And His First Murder

Born Edward Theodore Gein on August 27, 1906, in La Crosse, Wisconsin, Ed came of age under the influence of his religious and domineering mother, Augusta. She raised Ed and his brother Henry to believe that the world was full of evil, that women were “vessels of sin,” and that drinking and immortality were the instruments of the devil.

Augusta tied many of her teachings back to the Bible. Every afternoon, Gein and his brother would hear their mother read from the Bible, usually from the Old Testament of the Book of Revelation.

Despite his mother’s harsh style and domineering treatment of her sons, Gein came to idolize her.

Frantic to protect her family from the evil which she believed lurked around every corner, Augusta insisted that they move from La Crosse — a “sinkhole of filth,” she thought — to Plainfield. Even there, Augusta had the family settle outside of town since she believed that living in town would corrupt her two young sons.

As a result, Ed Gein only ever left his family’s isolated farmhouse to go to school. But he failed to establish any meaningful connections with his classmates, who remembered him as socially awkward and prone to odd, unexplained fits of laughter. What’s more, Ed’s lazy eye and speech impediment made him an easy victim of bullies.

Despite all this, Ed adored his mother. (His father, a timid alcoholic who died in 1940, cast a much smaller shadow over his life.) He absorbed her lessons about the world and seemed to embrace her harsh worldview. Though Henry sometimes stood up to Augusta, Ed never did.

So, it’s perhaps not a surprise that Ed Gein’s first victim was likely his older brother, Henry.

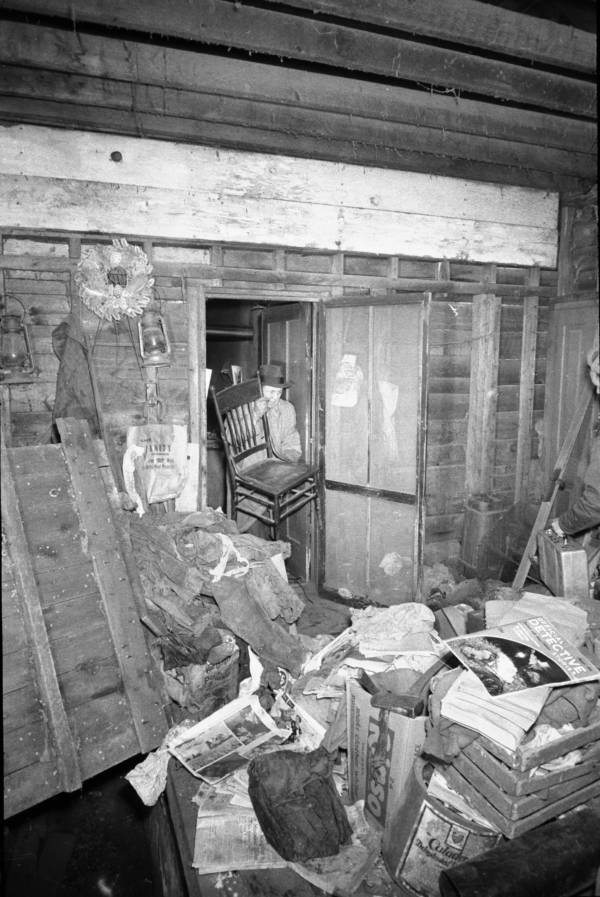

Bettmann/Getty ImagesEd Gein’s farmhouse, where he collected body parts for over a decade and used bones and skin to make gruesome objects.

In 1944, Ed and Henry set out to clear some vegetation in their fields by burning it away. But only one of the brothers would live through the night.

As they worked, their fire suddenly got out of control. And when firefighters arrived to put out the blaze, Ed told them that Henry had vanished. His body was found soon afterward, face down in the marsh, dead from asphyxiation.

At the time, it seemed like a tragic accident. But accidental or not, Henry’s death meant that Ed Gein and Augusta had the farmhouse to themselves. They lived there in isolation for about a year, until Augusta’s death in 1945.

Then, Ed Gein began his decade-long descent into depravity.

The Horrific Crimes Of The “Butcher Of Plainfield”

Bettmann/Getty ImagesThe interior of Ed Gein’s home. Though he kept some rooms pristine in memory of his mother, the rest of the house was a mess.

Following Augusta’s death, Ed Gein transformed the house into something of a shrine to her memory. He boarded up rooms that she’d used, keeping them in pristine condition, and moved into a small bedroom off the kitchen.

Living alone, far from town, he began to sink into his obsessions. Ed filled his days by learning about Nazi medical experiments, studying human anatomy, consuming porn — though he never attempted to date any real-life women — and reading horror novels. He also began to indulge his sick fantasies, but it took a long time for anyone to realize it.

Indeed, for a full decade, no one thought much about the Gein farm outside of town. Everything changed in November 1957 when a local hardware store owner named Bernice Worden vanished, leaving nothing behind but bloodstains.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesEd Gein, whose chilling true story helped inspire The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, pictured in court after his arrest.

Worden, a 58-year-old widow, had last been seen at her store. Her last customer? None other than Ed Gein, who’d gone into the store to buy a gallon of antifreeze.

Police went to Ed’s farmhouse to investigate — and found themselves in the middle of a waking nightmare. There, authorities found what would later inspire horror movies such as Silence of the Lambs, Psycho, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

What Investigators Found Inside Ed Gein’s House

Getty ImagesTrooper Dave Sharkey looks over some of the musical instruments found in the home of Edward Gein, 51, suspected grave robber and murderer. Also found in the house were human skulls, heads, death masks and the newly-butchered corpse of a neighboring woman. January 19, 1957.

As soon as investigators stepped into Ed Gein’s house, they found Bernice Worden in the kitchen. She was dead, decapitated, and hung by her ankles from the rafters.

There were also countless bones, both whole and fragmented, skulls impaled on his bedposts, and bowls and kitchen utensils made from skulls. Worse than the bones, however, were the household items that Ed Gein had made from human skin.

Frank Scherschel/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesAn investigator carries a chair made of human skin out of Ed Gein’s house.

Authorities found chairs upholstered in human skin, a wastebasket made of skin, leggings made from human leg skin, masks made from faces, a belt made of nipples, a pair of lips being used as a window shade drawstring, a corset made of a female torso, and a lampshade made from a human face.

Along with the skin items, police found various dismembered body parts, including fingernails, four noses, and the genitals of nine different women. They also found the remains of Mary Hogan, a tavern keeper who’d gone missing in 1954.

Frank Scherschel/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesEd Gein’s bedroom, in a state of extreme disarray.

Ed Gein readily admitted that he’d collected most of the remains from three local graveyards, which he’d started to visit two years after Augusta’s death. He told police he’d gone to the graveyards in a daze, looking for bodies that he thought resembled his mother.

Ed also explained why. He told authorities that he had wanted to create a “woman suit” so that he could “become” his mother, and crawl into her skin.

How Many People Did Ed Gein Kill?

Following the police visit to Ed Gein’s house, the “Butcher of Plainfield” was arrested. He was found not guilty by reasons of insanity in 1957 and sent to the Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Then, his farmhouse mysteriously burned to the ground.

JOHN CROFT/Star Tribune via Getty ImagesEd Gein being led away from his house in handcuffs after admitting that he’d killed two women.

Ten years later, Ed was deemed fit to stand trial and was convicted of the murder of Bernice Worden — but just of Bernice Worden. He was never tried for Mary Hogan’s murder because the state allegedly saw it as a waste of money. Ed was insane, they reasoned — he would spend the rest of his life in hospitals either way.

But that raises a chilling question. How many people did Ed Gein kill? Until his death in 1984 at the age of 77, he only ever admitted to murdering Worden and Hogan.

But it is possible Gein didn’t stop there. At the time, investigators suspected Gein was involved with the disappearances of four additional people.

The first of these disappearances was eight-year-old Georgia Jean Weckler, who disappeared from Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin on May 1, 1947. That afternoon, the young girl received a ride home from school from a neighbor.

The neighbor dropped off Weckler on Highway 12, near the road that led to the Weckler farm. However, she never made it home. She was last seen opening her family’s mailbox. Witnesses say there was a dark-colored 1936 Ford Sedan — and Ed Gein owned a 1937 Ford Sedan.

Another young girl, Evelyn Grace Hartley, was 14 years old when she went missing on October 24, 1953. She was babysitting for a La Crosse State College professor that night. Hartley’s father planned to call at 8:30 p.m. to check in on her, but she didn’t pick up his call.

Concerned for his daughter, he drove to the professor’s house to make sure everything was ok. When he arrived, the doors were locked, but the lights and the radio were on. He entered the house, and saw the furniture had been moved, as well as his daughter’s belongings.

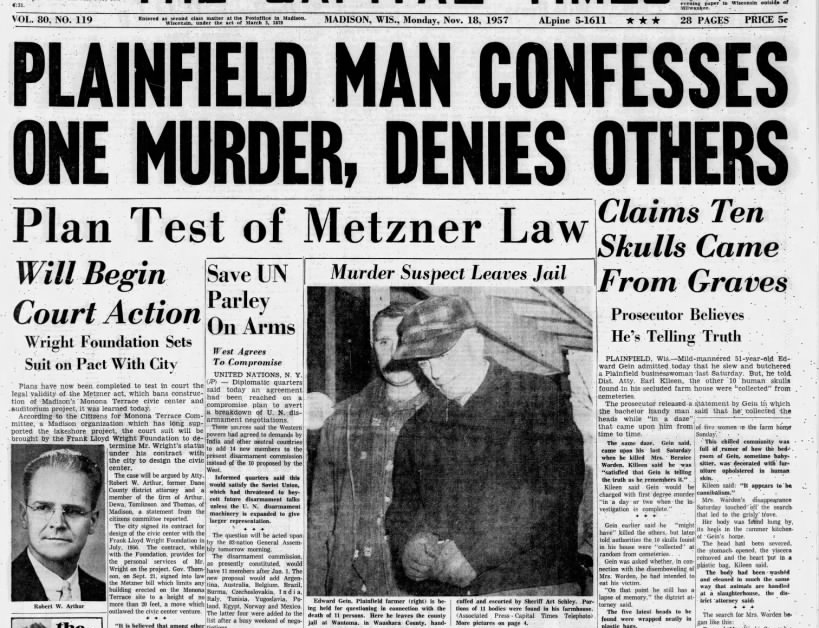

The Capital TimesThe front page of The Capital Times from November 1957.

Her shoes were separated — one was downstairs, while the other was upstairs — and her glasses were broken. Hartley was nowhere to be found. Gein was questioned about her disappearance and investigators looked for her remains in his home, but they couldn’t find a trace of her at his property.

Investigators also suspected Gein in the disappearance of Victor Harold Travis, a 42-year-old man who had been hunting near Gein’s property, despite being told not to. Travis disappeared on November 1, 1952 alongside Raymond Burgess after stopping at a bar in Plainfield. They left at around 7:00 p.m., and neither the pair nor their car was ever seen again.

The last disappearance that Gein was suspected to be involved with was that of his neighbor, James Walsh, in June 1954. After Walsh went missing, Gein would visit his wife to help out with chores around the house.

Gein was officially exonerated from any involvement in these deaths or disappearances after passing a lie detector test administered by investigators. Psychiatrists also concluded that it seemed his violence was only directed at women who resembled his mother. The other bodies found on Gein’s property — and police found as many as 40 in his home — he claimed he’d robbed from graves.

The Ultimate Fate Of Ed Gein After His Grisly Crimes Were Finally Uncovered

In the end, we may never know how many people fell victim to the Butcher of Plainfield.

With only one count of murder brought against him, Gein pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. He was indeed quickly found to be mentally unfit to stand trial and was sent to the Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, then to the Mendota State Hospital in Madison.

It wasn’t until 1968 that Gein was deemed fit for trial, a one-week affair that was held without a jury at the request of the defense. The judge found Gein guilty of Worden’s murder, but then a second trial quickly found him not guilty by reason of insanity, and he was returned to Mendota.

Ultimately, Ed Gein died at Mendota on July 26, 1984 at age 77 due to respiratory failure related to lung cancer. He was interred with his family at Plainfield Cemetery, but after repeated thefts and acts of vandalism, his gravestone was removed, leaving his burial currently unmarked.

To this day, Ed Gein stands as one of history’s most disturbing serial killers. He’s also seen as the inspiration for the mother-loving Norman Bates of Psycho, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre‘s skin-wearing Leatherface, and The Silence of The Lamb‘s Buffalo Bill.

Those movies have terrified generations of movie audiences. But they aren’t quite as chilling as the real-life story of Ed Gein himself.

After learning about the disturbing crimes of Ed Gein, read about still-unsolved case of the Cleveland Torso Murders. Then, read up on the horrific crimes of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer.

My Father Was a Serial Killer. I Was the One Who Turned Him In.

In Raised by a Serial Killer, April Balascio shares how she finally put the pieces together that Edward Wayne Edwards was not just a bad father, but a fundamentally bad person—and how she made the agonizing decision to tip off the police.By April BalascioPublished: Dec 05, 2024 11:29 AM ESTSave Article

Our editors handpick the products that we feature. We may earn commission from the links on this page.Jonathan Easterling

Iwas eleven when I came to realize that my father was a bad man, and that he was sometimes a bad father—a really, really bad father. Until then, he was just my dad and I loved him even while I feared his terrifying temper. But it’s not that simple, is it? It never is.

In 2009, I was a parent myself, living in an immaculate four-bedroom house that my husband and I had painstakingly renovated, with a four-car garage on five acres. Each of my three well-fed, well-dressed teenagers had their own bedroom. But I didn’t feel like I had arrived at some pinnacle of success. My husband worked the swing shift, and my nights were long. Questions about my past nagged me. My childhood was like a jigsaw puzzle I couldn’t put together because there were too many missing pieces. I couldn’t even re-remember all the names of the towns we lived in, but at night, unable to sleep, I’d lie in bed and try to remember each school I attended as a child—a new one almost every year—as a mental exercise, but also as something more. I was looking for clues. Why had we left all those towns in such a hurry? I had vague memories of rumors of missing people, of bodies found. Did those dark murky echoes have anything to do with my childhood? When I remembered a town name, I’d sit up, grab my laptop, and obsessively scan my computer’s search results for cold cases there. Each time, I was discouraged. Nothing struck me as significant or familiar. I was convinced I would never put my splintered memories back together. But one night, out of the blue, the name Watertown, Wisconsin, came to me. We weren’t there long, just the summer of 1980. I was eleven, but I remember with a strange clarity the old rambling farmhouse we stayed in there. It had an incongruous, giant stained glass window through which shards of colored light danced on the dining room table and floor.

I Googled “cold case 1980 Watertown Wisconsin.”

More From Oprah DailyTrailer: Kelly Casperson Rethink Menopause

Watch Full Video

A case called “The Sweetheart Murders” came up on my screen. With my pulse pounding in my ears, I read a news story about two young people who disappeared on the night of August 9, 1980, after attending a wedding reception just outside Watertown, in rural Jefferson County, Wisconsin.

According to the article, nineteen-year-olds Kelly Drew and Timothy Hack were high-school sweethearts. He was a farm boy who loved tractor pulls. She was a town girl who had just received a cosmetology degree. And they were last seen alive at 11 p.m., leaving the wedding reception at a venue called the Concord House. Six days later, strips of Kelly’s shredded clothing were found alongside the country road leading away from the Concord House, with dried semen on her pants and underwear. Their bodies were not discovered for two and a half months. Kelly’s corpse was found by squirrel hunters at the edge of a field, eight miles away from the Concord House. The police found Tim’s body not far from hers. Tim had been stabbed. Kelly had been bound and strangled and possibly raped. Despite one of the largest manhunts in the history of Wisconsin, the police were unable to find the killer.

I had vague memories of rumors of missing people, of bodies found.

I felt a shudder of recognition. The Concord House. We had camped next to it when we first moved to Wisconsin, and my dad had worked there. We moved into the beautiful old farmhouse that summer. I remember hearing that two teens in town went missing. Though we’d only arrived in Watertown a few months earlier, we left the state soon after the news broke.

In 2009, Jefferson County, Wisconsin, reopened the Sweetheart Murders case because there was biological evidence on file and they were asking the public for any leads. Flashes of déjà vu bombarded me. I could almost hear my memories clicking into place. But I was also afraid that what happened next would be like a row of dominoes. Once I tipped the first one, I wouldn’t be able to stop the outcome, even if I wanted to.

The cold case website gave a number to call with any information on the murders. I tossed my laptop aside and leaped out of bed. I paced my bedroom from window to window, to my mirror on the wall, back to the windows, back to the mirror, stopping to stare at my reflection. My hair stood on end from running my trembling hands through it again and again. It was late in the evening. I thought I might just call the number and leave a message. Surely, I wouldn’t have to talk to anyone.

Instead, I called my sister. She was only four when we left Wisconsin, so I didn’t expect her to corroborate my memories. I just wanted her blessing. But she was wary. “Think of what it will do to our families,” she warned. She was thinking of hers and mine, but also of our three brothers, and Mom and Dad, of course. But I was thinking of Kelly Drew’s family. Of Tim Hack’s family. And there were others, I was sure of it, if only I could put all the missing pieces together.

My sister’s words of caution unintentionally had the opposite effect. I was thinking about all the parents whose children never came home. My oldest son was nearly the age Tim had been on the night he’d died. My daughter was only a few years younger than Kelly had been. Like most kids their age, mine often went out at night with friends, and on those nights I felt a kind of dread beyond what was anywhere near reasonable. With my own children safely asleep in their rooms down the hall, how could I dare stay silent? How could I make any other decision? I told my sister I would think about what she’d said and hung up, but I had already made up my mind.

I dialed the hotline number, while mentally composing the message I’d leave, something vague like: “Hi, my name is April. I might have information on the Sweetheart Murders.” Then a voice answered, “Hello, this is Detective Garcia.” And the first domino fell.

A June 21, 2010, an AP article about the twenty-minute sentencing in Wisconsin after his confessions described Dad as “impassive, with head down.” The courtroom was packed with family members of Kelly Drew and Tim Hack. Kelly’s mother was quoted as saying to my father, “You are a lying, evil murderer and God is saving a special place in hell for you.”

On March 8, 2011, Dad was sentenced to the death penalty in Ohio. His execution date was set for August 31. But on April 7, Dad died of natural causes. His own body betrayed him, robbing him of his final performance. It was a small blessing that we—his children, grandchildren, and his wife—were spared the circus.

There were others, I was sure of it, if only I could put all the missing pieces together.

He died alone in his jail cell.

When I made the hotline call that night in 2009, I lifted the lid off Pandora’s box, and for some of my siblings, it seemed that I was the one who had done something unforgivable. Not my father’s crimes, but my revelation of them, was responsible for our fractured family. I do feel guilty for that. I also feel guilty I didn’t come forward sooner. If I had put it all together sooner, might others have been saved?

My love of animals was something I shared with my father, but he didn’t know how to care for them. Even then I knew that dogs and horses should be tended and cared for beyond being given food and water. He didn’t know how to care for children, either. But each of his five children figured out how to care for themselves. Each of us has led upstanding lives and given back to our communities. We’ve all had steady jobs and nice homes. I have those things, but they are not enough to make me stop digging into my father’s past crimes—he will be a puzzle I’ll always want to solve.

I may not know many more facts than I did when I started, but in shedding light on my father’s life, I illuminated my own. I’ve learned so much from the generous people who have gone on this journey with me. I’ve learned the power of forgiveness, and that if you don’t forgive the people in your life, it leads to bitterness and a hard heart. I forgive my parents.

I’m finding it more difficult to forgive myself. Do I want to be forgiven for betraying my father? Yes. But I think that’s something only I can grant myself. I’m working on it. And I’m feeling like the future holds promise.

Raised by a Serial Killer, by April Balascio

Now 52% Off

Adapted from RAISED BY A SERIAL KILLER: Discovering the Truth About My Father by April Balascio. Copyright © 2024 by April Balascio. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.