Why Do We Hate Women’s Voices?

How I reclaimed mine.

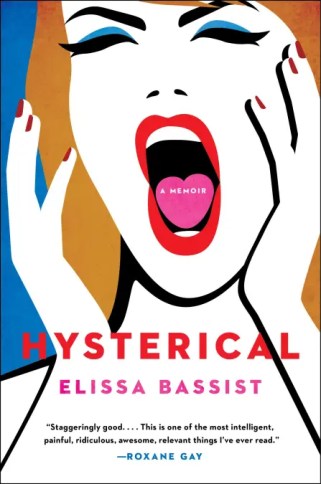

This essay was adapted from Hysterical: A Memoir, by Elissa Bassist, out September 13, 2022, from Hachette.

Everyone hates the sound of a woman’s voice. The “nominal problem is excess,” wrote author Jordan Kisner in The Cut in 2016. “The voice is too something—too loud, nasal, breathy, honking, squeaky, matronly, whispered. It reveals too much of some identity, it overflows its bounds. The excess in turn points to what’s lacking: softness, power, humor, intellect, sexiness, seriousness, coolness, warmth.”

And that’s just for white women. There’s also “too Black” and “too blue collar” to be credible and audible.

I began hating the sound of my voice at five years old, when I was ride or die for The Little Mermaid, the 1989 Disney classic about a teenage fish-princess who had everything but wanted more, so she signs away her best-in-the-world voice for long legs to pursue a boy with a dog. For ten thousand hours I memorized each song, and each song was my gospel. Especially the banger “Poor Unfortunate Souls,” in which the octopus witch Ursula sing-splains how human men aren’t impressed by conversation and avoid it when possible. I wanted to sing full-throttle like Ariel and then stop speaking for a boyfriend like Ariel had. I would not blabber or gossip or say a word! Besides, at five I had my looks, my pretty face, and I would never underestimate the importance of body language.

Anyone who grew up watching TV shows on a television in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s grasped at least three things: Men have a voice. Women have a body. Mentos are “the Freshmaker.” I was born the year the original Ghostbusters premiered (1984), and whenever I turned on something—TV, VHS, radio—the male voice was talking, coming out of everywhere as the mouthpiece of humanity, the soundtrack to existence.

For the next four decades I workshopped my voice to create the persona I wanted. Or the persona I thought I wanted. Or the persona I thought everyone else wanted. Even now, as a teacher and almost-famous writer, I must still speak in a world where a woman’s voice is both too much and never enough. So I started investigating why that is, and how I and other women found ourselves in this cage in the first place.Men have a voice. Women have a body. Mentos are “the Freshmaker.”

“An analysis of prime-time TV in 1987 found 66 percent of the 882 speaking characters were male—about the same proportion as in the ’50s,” writes Susan Faludi in her tome Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. Recent analyses by Martha M. Lauzen, a professor of film and television at San Diego State University who has tracked women’s employment in filmmaking and television since 1998, shows the percentage likely hasn’t really budged. Men even talk the most in rom-coms, billed as “chick flicks” made for women and starring stick figures known as women.

My mom and stepdad have a television hooked to cable in every room in the house. The three of us watched TV together during dinner, in a loud silence, and watched TV separately after dinner. Before bed the upstairs televisions switched to late-night TV talk shows, which men have hogged since the invention of television in the 1940s, and men’s jokes were the last thing we heard before falling asleep.

At dinner we were glued to Entertainment Tonight or TV news that starred white men who barked at each other and a few blonde bombshells. (Brunette women did not address the public about current events.) Then, like now, mostly men reported the news, and the news stories were mostly about men and were backed up mostly by men as experts and sources, anointed as thought leaders to tell us all the truth. Star news anchor Chris Cuomo might have reported on the heyday of executive producer Harvey Weinstein, which legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin would then corroborate.

If and when news outlets did talk about women, it didn’t seem as if they had anything nice to say. In my thirties my Democrat parents said in unison, “We don’t like Hillary Clinton,” repeating the cable news they ate for every meal. In the 2016 and 2020 election cycles, female presidential candidates received less overall coverage than men and more negative coverage than men, and much of the criticism came down to voice and how men can and should raise their voices but women need to calm down. During the 2020 vice presidential debate, not only did then senator Kamala Harris repeat (have to repeat), “I’m speaking,” but also moderator Susan Page let Mike Pence speak longer, interject more, ignore her, and moderate the debate himself by asking his own questions. As Politico reported: “She repeatedly tried and failed to get Pence to stop talking, saying variations of ‘thank you’ or ‘thank you, Mr. Vice President’ 22 times over the course of the evening, to no effect.”In 2016 and 2020, female presidential candidates received less coverage than men and more negative coverage than men, and much of the criticism came down to voice.

“In group settings men are 75 percent more likely to speak up than women,” says Dr. Meredith Grey in season 12, episode 9, of Grey’s Anatomy. (If you’re anything like me, then everything you know about the medical establishment, gender dynamics, and hooking up you gleaned from nineteen seasons of Grey’s Anatomy.) In “The Sound of Silence,” Dr. Grey (who is assaulted and beaten to the point of being physically unable to speak in this episode) stands in front of a group of interns and asks a question. The male interns take up most of the room and raise their hands to answer. Not one woman raises her hand. Each looks scared to speak. This scene could be any classroom or meeting or drinks with heterosexual cis men, who, per evidence ad infinitum, are actually “too much” because they speak the most and the loudest and the longest; they say what a woman is on the verge of saying or repeat what a woman just said (but with more confidence or rudeness); they take more credit and interrupt more (but call it “cooperating”), then perhaps apologize, sincerely or not, and justify themselves, at length.

Meanwhile, women use their voices to help men use theirs. Sociolinguist and professor of linguistics Janet Holmes cites research in her 1998 essay “Women Talk Too Much,” anthologized in Language Myths, that “men tend to contribute more information and opinions, while women contribute more agreeing, supportive talk, more of the kind of talk that encourages others to contribute.” Melissa Febos in her collection of essays Girlhood, writes, “A trans woman friend of mine recently explained to me how the technique for training your voice to sound more feminine has a lot to do ‘with speaking less or asking more questions or deferring to other people more.’” The discipline of desirability is also the discipline of submission.

As a kid I believed women just didn’t talk that much. Or shouldn’t. Or couldn’t? This is because of a feedback loop: Boys talk more than girls in three-quarters of Disney’s princess movies—and boys speak more than girls in the classrooms, and men speak more than women in work meetings.

But once I grew out of The Little Mermaid and my fantasy of silence and sailing away from my family as a royal child bride, I had a new ideology about a girl’s voice: It should sound like a boy’s.

In fifth grade to be a tomboy was the tits, and to be “cool” was to be “down” with what boys said and liked. The secret code to being one of the guys—whose approval I sought because the universe said I needed it—was to suppress or erase all signs of girlhood. To graduate girldom, I watched South Park and memorized Pulp Fiction, wore Umbros and Adidas, read R. L. Stine and Mark Twain, listened to Dre and Snoop, leveled up in math classes (aka boys’ classes), wallpapered my room with posters of sports I wasn’t allowed to play, camped outdoors and peed standing up while camping, liked guys who’d liked Green Day before Green Day sold out, talked in drag and cursed like a dickhead, and masked my true tastes, point of view, and attitude to align with boys’ tastes-POV-attitude.

I kept experimenting. In middle school I reverted to being a girly drama queen—but also depressed because my voice was so nails-on-a-chalkboard, so full of so many feelings there was no room for anything else; it sounded like a tampon if a tampon talked. I realized I’d made a huge mistake, so in high school I joined the speech and debate team, and once more made every effort to talk like the boys, because when boys talked, everyone listened. Boys’ talk let them be understood, and their voice existed for only themselves. Even today’s automated speech recognition technology, like virtual assistants and voice transcription, is more likely to respond to the white male cadence. About voice recognition in cars that don’t recognize women’s voices, one male VP of voice technology suggested women fix their voices “through lengthy training” to “speak louder” and to “direct their voices towards the microphone.”Today’s automated speech recognition technology is more likely to respond to the white male cadence.

After school I’d talk to myself in the mirror in my own “lengthy training,” rehearsing a chiller but louder and lower voice, a voice that was sensible and cocksure and won video games and masturbated into a sock.

I wasn’t born into the wrong body. I was born into the correct body in the wrong world.

In this world Margaret Thatcher took voice-lowering lessons to deepen her pitch to sound firmer and more powerful and as if she had a cold and a penis in order to be taken seriously. Elizabeth Holmes appeared to fake a baritone to attract investors and scam them. A National Public Radio cohost told me that several radio women take voice-lowering lessons and that producers tweak women’s timbre and enhance their bass on air—all due to listeners’ complaints. Since the male voice is the voice of every generation, a lot of us find ourselves speaking with it (the average woman today talks in a deeper voice than her mother and grandmother), re-tuning our voices to put us in league with self-described gods.

With my less-feminine voice I became speech co-captain and spoke at graduation, about The Simpsons and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by male author Robert M. Pirsig, and was the sole girl to be nominated for the end-of-high-school superlative “Most Likely to Be Successful” (I lost to a boy). At last, I had a voice; it just wasn’t mine.

When asked about “the heroine’s journey,” Joseph Campbell, the originator of “the Hero’s Journey,” purportedly said, “Women don’t need to make the journey. All she has to do is realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to.”

My male high school speech coach coached me to wear my hair curly during male-dominated competitions. “It’s sexier,” he said in an empty school hallway. I hadn’t yet realized I was the place that people are trying to get to.

I realized this in college.

In college I underwent yet another transformation, like a second cycle, but instead of evolving from girl to woman, I changed from subject to object, from person to place. A deeper voice didn’t fly—it was in an unfuckable octave, and men couldn’t hear me (again) or, it seemed, didn’t care to.

So, I grew another. At parties I spoke in a combination of high pitch, vocal fry, uptalk, and broken sentences that curled. A “sexy baby voice.” Men liked this voice. It was horny yet nonconfrontational. It was defenseless and signaled that I must be protected and coddled and burped. Actual research shows that this higher voice coming out of a female body is perceived as more agreeable and much hotter. Vocally and weight-wise, infancy is apparently a woman’s sexiest time. The anti-voice is so adored that voice assistants like Siri and Alexa default to feminized voices based on retrograde stereotypes of subservience.

“I’d blush if I could,” Siri says to sexual commands, while Alexa responds flirtatiously when verbally abused. (“Men Are Creating AI Girlfriends and Then Verbally Abusing Them” is a recent headline about “chatbot abuse.”) Artificial-intelligence-powered voices don’t yet have the porno mode that comes standard in real women, in me, which was part of my college realization.

I got good at changing my voice, as if it were outfits. But it felt like a curse, almost, the way the legs of my voice could spread or shut, the way I could sound helpless and open to suggestion and to being walked all over and ignored everywhere but the bed and the crib.

“Sorry to interrupt,” a student, a male student, my male student said to a female student in the class I was teaching as an adult woman thirteen years post-college. After he interrupted her, he corrected her opinion, and she and I exchanged identical just-punched looks.

“When a woman does speak up,” Dr. Meredith Grey continues in voiceover in the same Grey’s Anatomy episode, “it’s statistically probable that her male counterparts will either interrupt her or speak over her.”

I called out my male student, in my nicest tone of voice, and the next day he emailed me for calling him out. He “just wanted to take a quick second” to tell me why he interrupted “that other student.” “There was a reason for it,” he wrote. He “felt like we were getting dragged off topic quite a bit,” and he “could feel that we were really slipping behind schedule.” A former student had told him “how much fun it was to do the pitches and I wanted to make sure we had time for that.” In the next paragraph he concluded, “So that was why I [interrupted]. I was trying to help you. But it obviously didn’t come off that way, so I apologize.”

I didn’t reply, didn’t point out that he’d come to class thirty minutes late, didn’t ask why he didn’t take notes and instead smiled at me for three hours, didn’t correct him about how we weren’t off track because people are allowed to talk in class, didn’t remind him that I can teach my own class by myself, and didn’t yell at him— a white guy—about his pitch, a satire about slavery. Saying or doing any of the above, my colleagues and I agreed, would’ve made things worse because it would have provoked him to send more emails.

Right now women are being interrupted—or undermined or spoken for or misinterpreted—in classrooms across the world, if they’re lucky to be in one. “It’s not because [men are] rude. It’s science,” Dr. Grey says about interrupting women. “The female voice is scientifically proven to be more difficult for a male brain to register.” It isn’t only because of systemic sexism that women are hard to hear; it’s science.

Except it isn’t. The fictional Dr. Grey’s scripted dialogue is pseudoscientific and likely based on the oft-quoted study “Male and Female Voices Activate Distinct Regions in the Male Brain,” conducted by all men using all male subjects and described as men versus women arbitrarily (it could have been described in any number of ways, like lower pitch versus higher pitch). Whether women are harder to hear (we’re not), or people just don’t want to hear women (it’s this one), the onus is on women to be heard.

Before teaching and after a lifetime of moving my voice up and down into the impossible “right register” to be heard, I became afraid of my voice, like the fictional women surgical interns in Grey’s Anatomy. My fear of speaking could be understood as a personal dysfunction, or it could be understood as a generalized response to women being interrupted or censured for speaking, such that a woman’s fear system perceives any and every act as a fight waiting to happen and to prevent.

Because, of course, men do more than interrupt us. Homicide and rape statistics show that a woman should fear her voice—there’s even the term “rejection violence” for the specific phenomenon of abusing, stabbing, shooting, raping, gang-raping, murdering, and mass-murdering women for saying no. And the unrecorded statistics of violence against BIWOC and LGBTQ people imply that marginalized groups should be even more afraid of their voice and, as Tressie McMillan Cottom writes in Thick, be more obliged to “screen our jokes, our laughter, our emotions, and our baggage” and “constantly manage complex social interactions so we are not fired, isolated, misunderstood, miscast, or murdered.”“Is there therapy for women with Patriarchy? I’m asking for every friend I have.”

I started seeing a therapist about my voice, and about how I had begun to silence myself compulsively. I asked my therapist, “Is there therapy for women with Patriarchy? I’m asking for every friend I have.” I was asking also for myself, a woman who couldn’t pronounce the two-letter word “no” and who gave men whatever they wanted. And I was asking for my creative writing students, who, if they’re women and they do speak up in class, it’s to disclaim their writing and lived experience, as though their free speech and their license to live and to comment on living is in perpetual question, as though their writing is our millstone and their perspective is beside the point in a class they paid to participate in, a class where I beg women to ask questions because I’d have to be begged if I weren’t the instructor.

There isn’t therapy for patriarchy, so far. Whenever my therapist and I came to these conclusions, we’d look blankly at each other and shake our heads until our time together was up.

“Nothing will come of nothing,” says the dad King Lear to his youngest daughter, Cordelia, in words written by male playwright William Shakespeare. “Speak again,” he tells her. How, exactly, to speak again? How to do what women have been conditioned not to do? How to go against every instinct and societal directive in a world that prefers a woman’s death to her opinion?

Author bell hooks had to change her name. “One of the many reasons I chose to write using the pseudonym bell hooks,” she wrote in Talking Back, “was to construct a writer-identity that would challenge and subdue all impulses leading me away from speech into silence.”

French feminist writer Hélène Cixous thought that to reclaim their voices, women must reclaim their narratives: “Women must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies—for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal,” she wrote. “Woman must put herself into the text—as into the world and into history—by her own movement.” I needed to put myself into text to put myself back into the world.

And to bring back my voice from the dead—to say what I wanted without fear of disaster or error, and without a frantic, overwhelmed lurching, and aside from whatever would happen, or wouldn’t—first I needed to get back to “no.”

My therapist had me practice by messaging “no” on dating apps—to get used to it and get in the habit, to drop the carefulness that looks like agreement when I do not agree, and to not give in to the inclination (the pressure, the imperative, the survival mandate) to indulge a man just because he’s a man.

“Hey Elissa, keeping busy?” a man on Bumble (or Tinder or BeLinked or Fuck, Marry, Kill or one of a thousand other dating apps) messaged. I thought, No, but feared being rude, and because of the potential for rejection violence, I feared rude’s attendant outsize fear of being murdered.

“Lean into your fear,” my therapist prompted me. She wasn’t talking about Sheryl Sandberg’s mission in Lean In. She meant that whenever I questioned my words, I should reiterate “lean-in statements” to practice having a non-compulsive response and to agree to my fear and doubt instead of fight or flee or freeze or fawn.

I reread “Hey Elissa, keeping busy?” and typed, “No,” then hesitated.

“You must be willing to feel some discomfort,” the clinician said in a ruthless manner.

I leaned in. Maybe I am rude. Maybe I will be murdered for being rude. Then I tapped the paper-airplane icon and my “No” appeared on the screen.

The next thirty seconds I was in turmoil sitting with uncertainty—I said the wrong thing, didn’t I? DIDN’T I? Did I?—and trying not to bail by coping mechanism. Because that’s what I had to do, what I did do and would do infinite times, like a redwood tree that must burn to grow.

“Hey! are you into films? Have you seen the new joker movie?”

“No.”

“Elissa! Hello! Tell me, would you rather be a master of all instruments or be able to speak any language fluently?”

“What? No.”

“20 questions! You have to give honest answers and you can’t repeat any questions the other person asked. Deal?”

“20 answers! No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No.”

“We should meet up tonight”

“I’m not ready to meet up yet”

“Merci Elissa, okay I understand when do you think you will be ready?”

Each time I said no, it was the end of the world, until it wasn’t. With every no, my anxiety and rage dissipated, and I could almost feel distress purify through repetition.

“No” is still slippery. But when it’s accessible—and it’s more and more accessible—I feel as if I can do anything. Like trust myself.

Speaking again is not easy, but it’s simple. “It’s risk,” my therapist tells me.

Risk “no.” Risk being unlikeable and being perceived as unreasonable, and risk being called a fucking bitch. Risk “being a bitch.” Risk “bad” words. Risk mistakes and risk being corrected and risk losing those who won’t forgive. Risk refusal. Risk acknowledgment. Risk trouble. Risk the question. Risk demanding care. Risk a voice that doesn’t demure, a voice that is difficult, unaesthetic, charged, forthright, sappy. Risk it, or risk living a half-a-person life.

Copyright © 2022 by Elissa Bassist. Reprinted by permission of Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc., New York, NY, USA. All rights reserved.

If you buy a book using our Bookshop link, a small share of the proceeds supports our journalism.

Maggie Rose’s “Girl In Your Truck Song” (A Rant)

Trigger Down with Pop Country 163 Comments

WARNING: LANGUAGE

What in the all kinds of actual hell do we have here my friends. I think we have just unearthed the biggest cultural abomination that has ever been classified as “country” music in its 70 year existence. No, I’m not talking bad, awful, terrible, or any other such adjectives. Even those words would seem to instill this embarrassment of Western Civilization with a dollop of undeserved respect. Truth be known, there are songs that officially sound worse than this one out there for sure, or that are more stupid either purposefully or inadvertently. But the degree of slavitude and cultural backsliding celebrated and edified in this song is as abhorrent as it is alarmingly calamitous, and hovers only very slightly, and uncomfortably so, above genuine calls of gender downgrading and the erosion of sexual equality in American society, bordering on downright pleas for date rape. I am severely embarrassed that I have poured my lifeblood into something that utilizes the term “country” in a world where this song exists, and pray that I have the strength to steady my hands enough to coherently compose just how angry this song makes me.

But get this ladies and gentlemen. Before we even get into the heart of this matter, sit back and appreciate that the same exact day the brand new female country duo Maddie & Tae released their first single ever called “Girl In A Country Song”, whose verses include lines and titles of actual “Bro-Country” songs, young Maggie Rose released her song called “Girl In Your Truck Song” …. WHOSE VERSES ALSO INCLUDE LINES AND TITLES OF ACTUAL “BRO-COUNTRY” SONGS.

Yeah, big oops by Music Row as they inadvertently pull the curtain back to expose the inner workings of their institutionalized conveyor belt formulaic and copycat songwriting rubber stamp machine laboring away. “Pay no attention to the man behind the green curtain” they say with blushing cheeks, as they pretty much just released the same exact fucking song, on the same exact fucking day, and from institutions that are only 0.8 miles away from each other on the same exact fucking street on Music Row; only one song has a negative take and the other has a positive one. If there has ever been a moment where the country music industry has trumpeted emphatically how stupid they think you are, this is it.

From the heartfelt yet respectful concerns of some for how young women were being portrayed in country songs, to downright calls of sexism being perpetrated in country music from the “Bro-Country” takedown of the genre, sincere worry was already being transmitted from many sectors about female’s devolving role in the country music format. Now this alarming trend takes a gigantic leap forward (or backward, as it were), as a young woman voluntarily puts herself directly in the path of the misogynistic and materialistic locomotive that is modern day country music by pleading with her overbearing beau captor to allow her to become the subordinate piece of meat that is portrayed in all the worst hits of the “Bro-Country” era.“Friday night I’m getting ready. Call you up so come and get me.I got my jeans on tight, I’m feeling sexy.Tonight, tonight …I want to be the girl in your truck song, the one that makes you sing along.Makes you wanna cruise, drink a little moonshine down, leave a couple tattoos on this town.Chillin’ out with a cold beer, yeah, hangin’ with the boys round here.Gonna take a little ride, That’s my kind of night.You and me getting our shine on, I wanna be the girl in your truck song.Gonna hop on in, so slide it over. Lay my head down on your shoulder.We can rev it up, or take it slow. I don’t care, I don’t care.”

As one studious observer on Twitter pointed out to me, women in country music have now become so marginalized, Stockholm Syndrome has set in. When Rolling Stone Country talked to Maggie Rose about this song, she said, “There are females embracing that role that all these men are writing about.”

What the fuck did I just read? That has been the concern the entire time with this “Bro-Country” bullshit, that having guys that learned how to treat women from 90’s hip-hop songs dominating country music would result in actual behavioral changes in young women. The entire time we’ve been told, “Don’t be so uptight, they’re just songs.” And here is Maggie Rose not only releasing a song that takes a further subservient step, but then she confirms this is how young women are reacting to this trend, and they’re doing so “all over the country.”

Then Maggie Rose goes on to say, “Don’t fight it; embrace it.” Huh. Is it just a coincidence that these are the same exact creepy words a date rapist utters as he has his way with someone’s daughter?

Oh and get this: Preeminent “Bro-Country” songwriter Dallas Davidson took time from having narcissistic knuckle-chucking and homophobic-fueled meltdowns in Nashville’s douchiest fern bars to co-produce this song, giving it that extra special touch of misogynistic flair.

I don’t want to be any more disrespectful to this young lady Maddie Rose than she has already been to herself by cutting this song. But I’m sorry, this is a abomination, and the fact that this isn’t obvious to every listener and Maggie Rose herself shows just how bereft the country music moral compass has become. This song should be met with stiff and spirited resistance from all sectors. Tyler Farr and “Redneck Crazy”, eat your heart out.

READ: Maddie & Tae’s “Girl In A Country Song” Anti Bro-Country?

And if I were to guess, I would say that Maddie & Tae’s “Girl In A Country Song”, written by the two girls themselves, truly came from original inspiration, however good or bad you want to consider it. This “Girl In Your Truck Song” was written by the songwriting committee of Caitlyn Smith, Gordie Sampson and Troy Verges, and would have to be fingered as the ripoff if there was one. But who knows, maybe it truly was as coincidink that the two songs sprouted at the same time. Nonetheless, “Girl In Your Truck Song” should have been left on the cutting house floor, and releasing it is nothing short of culturally irresponsible.