The appeal of boxing to its fans

This article is more than 12 years old

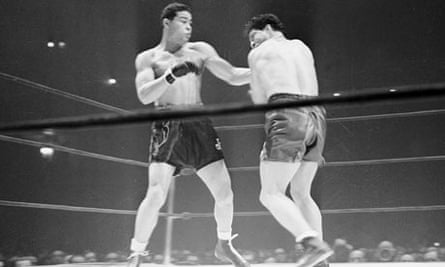

At its core boxing is about one man hurting another, but fans are lured to the sport in the hope that they will see a fighter overcome that pain and adversity and go on to triumph

Jeff Pryor for The Queensberry Rules, part of the Guardian Sport Network

When it comes to sports fans, boxing spectators are among the most vociferous and voracious. Part of that are the pitched battles and high stakes in the ring. There’s more on the line than in any other contest.

Men have lost their lives. The fear witnessing a tragedy provides a morbid fascination that many wouldn’t want to admit. The truth is that boxing is a sport that at its core is about one man hurting another.

But the appeal for most of us is not the pain that is being doled out. It is the hope that we will see someone overcome it, just as we strive to overcome the trials and tribulations in our everyday lives. These men, in distilled, compact, intensely concentrated dosages, face down adversity and strive to triumph. We look for the best of ourselves reflected in the fighters we follow.

Prizefighting is a sport where there are no barriers between the fan and the athlete. There is no helmet to hide their face. No pads to obscure their figure. No closed huddles or secret hand signals. No bandages for an injury.

The playing area isn’t a hundred yards long or a field of ice. It’s just a couple dozen feet. The ring is confining. It captures us. The ring is intimate. It invites us. The ring is wired. Speak and we hear it. The ring contains the action. It frames the action. The cameras don’t capture 10 men, or dozens scurrying around. Just two, in close up. And of those two, we have more access over the course of 36 minutes of action than we do for other athletes over the course of an entire season.We see their eyes. We see them think. We see them fight. We see them bleed. To paraphrase Joe Louis… you can’t hide in the ring. In fact, you can only show. Show your talent and skill. Show your heart, determination and will. And show whether you’ve got what it takes, on the night, in those moments of anxiety, pressure and strife.

The ring is a pedestal. We place the fighters on it and watch the proceedings. We hold them to unfathomable standards. We judge them fairly and unfairly… harshly and lovingly. The ring is a stage. An adaptation of our lives.

These factors connect us to boxing’s participants in a way that can be more powerful than any other sport. But what locks us in to a particular fighter over another? What makes a fighter your fighter? It may be as simple as a prizefighter hailing from the same geographical region as you do. We want to root for a hometown hitter – someone to represent us, give us ownership and pride. The geographical pull is so strong, in fact, that many a fight fan finds themselves cheering on a pugilist they ordinarily wouldn’t care for at all. Maybe you hate brash young trashtalkers… but this loudmouthed kid is from your proverbial backyard. Maybe you despise safety first technicians… but hell, this is a promising prancer from the next burg over. As your eyes are first opened to the sweet science, your choice in fighters is often a mere chance of fate.

Do you remember your first fight, the one that hooked you on boxing? There’s a good chance one of those fellas, in that moment of your personal history, became a fighter of great interest to you, simply because they had the honor of introducing you to one of the most compelling dramas humanity can stage.

Even a terrible fight can spark the imagination of the uninitiated. A few years ago Jermain Taylor and Cory Spinks faced off in one of the most boring, mind-numbingly dull and maddening middleweight championship bouts in history. But many Arkansans cheered on their state’s son, Taylor, while a host of others tuned in for Spinks, simply because he was repping St. Louis. While the fight was an action-less abomination, inevitably new fans were birthed that night too, energized by the sudden exposure to something intriguing, though rife with unfulfilled promise from the two hapless combatants. These new spectators left intrigued, but wanting more. Like some pent up teenagers inaugural night with a girl, their first time didn’t quite measure up to the mounting enthusiasm they’d started the evening with. But at the close of the show they’d seen what their future had in store. They’d glimpsed the tip of a hidden lust and of what future nights with two going at it could portend. These first fighters we follow are thrust upon us by chance or proximity. For the most part, however, we choose our preferred pugilists, consciously or unconsciously. And the choice has more to do with us, then them. Every fighter is a combination of three things: skill, athleticism and spirit. Prizefighters pull elements from across the spectrum of these strengths and weaknesses, but memorable fighters tend to be overloaded in one particular category. With skill, there is a level of professionalism implied. You know they take the sport seriously. They’re in fighting shape. Their fights may not devolve into all out action, because there is a certain level of restraint and control. They’re smart. They are thinking out there. Precision, timing, studying, adjusting. Machines. Then there are athletes, the specimens that were born and not created. Perhaps they are blessed with blazing speed or bludgeoning power, lightning reflexes or towering size. The fights could be suddenly explosive or eye opening. A lack of consistency overall is made up for with big KOs or flashy combos. The razzle, the dazzle; they enchant with effortless excitement engendered. And then there is spirit. A warrior who may not be the fastest, the biggest or the most skilled, but a fighter through and through. Courage and determination. When attacked, they attack. When knocked down, they get up. More pure in a way; more animal. Impassioned and inspirational. Each of us responds to one of these traits more than the other two. We gravitate towards the type of fighter we would be or aspire to be, were we to make our way into the ring. I admire technicians. They weren’t supermen to begin with, but they put in the work and made themselves into what they are through dedication and determination. In this way, Bernard Hopkins and Juan Manuel Márquez speak to me, pull my attention. I can see myself in the way they’ve gone about their careers. I’m cerebral… and these men think. They think about what they are doing. They think about what their opponent is doing, will do, might do… They are cool and calm, analyzing before, during and after the fight. Like finely tuned watches, they know when the time is right to make their move. And the time is right, because they have diligently prepared for it beforehand. Doesn’t mean I don’t greatly admire or root for a guy like Carl Froch who has shown grit, sheer aggression and a “throw caution to the wind” rambunctiousness that Hopkins or Marquez rarely have dug up in their careers, or that I don’t marvel at Adrien Broner’s laser strikes and athletic arsenal. Thing is, I just don’t relate to the mindset or talents of each on a personal level. The special fighters are those that bridge the different categories and become a figure that everyone can appreciate and see themselves in. Division-conquering maestro Manny Pacquiao reached his greatest level of universal acclaim and recognition, just as he bridged the gap between all three categories laid out above.

He entered our consciousness as the dynamic athlete, showed his spirit when tested and then rounded out his persona by dedicating himself to fine tuning his skills. He is a complete fighter in every sense of the word and in that light it’s no wonder just about everyone loves him; he appeals to every type of fan.

Former boxing action star Arturo Gatti crossed over in to most fans adulation because he was so extremely overloaded with an ungodly amount of fighting spirit. If someone had come to him before a fight to tell him he would be badly cut over both swollen eyes, his hand would be broken, and he’d be knocked to the canvas in the ensuing bout… he’d still choose to head into the ring. Such was the belief in himself that no matter how grim, or stacked against him he felt the odds, he could persevere. As a spectator, nothing more could be asked. Between athleticism, skill and spirit, the last is the most uniting among boxing fans. Spirit is something we all have in us. You don’t need any special knowledge of the sport to spot courage or willpower. It offers the most dramatic moments and it’s the only trait that can be directly transferable to those of us watching, as we rise from our seats and feel the passion infused moment crescendoing. Athleticism comes next on the scale of what drives our admiration. It’s exciting, awe inspiring and even if we aren’t world class athletes, we certainly wish we were. There’s also something innately satisfying at watching a virtuoso effortlessly do what he was born to do. Skill brings up the rear. Its appreciation comes with patience and insight. The toiling hours of dedication and diligence that foster this craft doesn’t quite fire the imagination like the other traits and so it lacks the flash and drama, but to see a technical marvel is like the difference between sighting the Eiffel Tower and the peak of a mountain; both reach great heights, but behind the handmade effort we can fathom and admire the work it took to build. With all this in mind, what has led us to the corner of a particular fighter is very apparent. It’s simply a variation on the idea posited in the film “Pulp Fiction”: “There’s two kinds of people in this world, Elvis people and Beatles people. Now Beatles people can like Elvis. And Elvis people can like The Beatles. But nobody likes them both equally. So somewhere you have to make a choice. And that choice tells you who you are.” We are drawn to certain pugilists naturally because of what we value. Some may be enticed by the violence and aggression of it. Others may like the artistry of the sweet science. Some may like the nostalgic quality of prizefighting and its far reaching history. What intrigues me is the psychology of the fighter, the mindset you must have to compete in the ring, shelving fear of injury, pain, embarrassment, failure… the ongoing struggle to triumph over those elements, on a second by second basis: Competing not just against the man across from you, but also against yourself. I watch for the subtle cues in a fighter’s demeanor as he wins those internal struggles, or begins to succumb to them. That’s what grabs me and holds me enthralled when the sport is at it’s best. If you want to see boxing as a barbaric bout of bashing fists you can. If you wish to see the noble sacrifice of a man providing for his loved ones you may.

Are you there to see punishment and punching, blood and brawling? Are you interested in triumph and tragedy, persistence and perseverance? The sport gives you what you bring to it, and the fighters you’ve chosen, often choose you. Boxing is man’s purest contest, its blankest canvas.

On it we paint, with punches of colour – blots of black and blue, spatters of crimson, hues of bursting vibrancy and streaks of vivid pigment. It is the reflective portrait of our dreams and failures, given faces and gloves, standing in for us and unfurling our hopes to be cheered and hoisted on shoulders, paraded in triumph that we share, aspire to and dream of.

In the end, you are not rooting for the man in the ring. You are rooting for yourself. Boxing’s victory is in making each of us its champion.

Sport and the Decline of War

How sport can help the human race transcend war and conflict

In 1910, shortly before his death, the eminent psychologist William James wrote an essay called The Moral Equivalent of War, in which he attempted to understand the human race’s apparent love of warfare. James argued that warfare was so prevalent because of its positive psychological effects. Put simply, it made people feel good.

One way in which it does this, according to James, is by making people feel more alert and alive. Both for soldiers and civilians, warfare lifts life to “a higher plane of power.” It enables the expression of higher human qualities which often lie dormant in ordinary life, such as discipline, courage, and self-sacrifice. Warfare creates a powerful sense of community, in the face of a collective threat. It binds people together and creates a sense of cohesion, with mutual goals. The “war effort” inspires individual citizens (not just soldiers) to behave honorably and unselfishly, in the service of a greater good.

James’ views might seem old-fashioned, based on a romantic notion of warfare which was no longer possible after the horrors of the First and Second World Wars. However, the New York Times war correspondent Chris Hedges identified the same effects while observing recent world conflicts. Hedges witnessed the bonding effect of being at war with a common enemy, and the transcendence of social conflict and dislocation. He also describes how war generates a strong sense of purpose and meaning, as he writes, “War is an enticing elixir. It gives us resolve, a cause. It allows us to be noble.”

James’ point in The Moral Equivalent of War is that human beings urgently need to find an activity which has the same positive psychological and social effects of warfare, but which doesn’t involve the same devastation—this is what he means by “moral equivalent.” Perhaps disappointingly, in the essay he is not very clear about what this might be. But from our vantage point in history, there is an obvious contender for a “moral equivalent of war”: sport.

Sport satisfies most of the same psychological needs as warfare, and has similar psychological and social effects. It certainly provides a sense of belonging and unity. Fans of soccer, baseball or basketball teams feel a strong sense of allegiance to them. Once they have formed an attachment to a team (usually during childhood) they “support” it loyally through thick and thin. The team forms part of their identity; they feel bonded to it, and a strong sense of allegiance to the other supporters, a tribal sense of unity. Sport also enables the expression of “higher” human qualities which often lie dormant in ordinary life. It provides a context for heroism, a sense of urgency and drama where team members can display courage, daring, loyalty, and skill. It creates an artificial “life and death” situation which is invested with meaning and importance far beyond its surface reality.

Sport can certainly lift life to a “higher plane of power” too. Watching a major sports match—e.g. a soccer match in the UK, or a baseball game in the US—is an empathic, rather than a passive experience. It is an experience of complete, passionate engagement, generating powerful emotional responses. (Although admittedly, this may partially depend on how exciting the game is.) At the end of the game, the spectator often feels emotionally drained, in a mood of euphoria or desolation (depending on the result).

The Decline of Warfare

If sport is a “moral equivalent of war” then it should be able to serve as a substitute for it, and to bring about a decline in warfare. Is there any evidence for this?

There are both small scale and large scale examples. In the second half of the 19th century, my home city of Manchester, UK, was gripped by an epidemic of youth gangs and knife crime. Large parts of the city were unsafe, as pedestrians could easily be caught up in fighting, and were often randomly attacked. But during the 1890s, a small number of enlightened people realized that the youths needed to be offered other outlets for satisfying their psychological needs other than gang membership and violence. They set up “working lads” clubs’ throughout the city, which gave the poorest slum youths access to sport and recreation. This led to a new “craze” for football (soccer) that spread rapidly through the city. (Indeed, it was during this decade that Manchester’s two famous modern soccer teams—Manchester United and Manchester City—were originally established.) As a result, youths who had previously fought against each other in gangs were soon “fighting” each other in football teams, both in “street football” and in organized games through the lads’ clubs. This suggests that the psychological needs which had given rise to gang membership and conflict, were now seemingly being channeled into sport—bringing a massive reduction in actual conflict and violence.

The same principle has been applied in the modern world too. In Columbia and Brazil, for example, the promotion of soccer in areas of high gang activity has led to a significant reduction in crime and violence.

On a global scale, the last 75 years have seen a steady ongoing decline in the number of deaths due to group conflict in the world as a whole (Human Security Report Project, 2006). Since the Second World War, there has been a massive reduction in international conflict (sometimes referred to as “The Long Peace”). In particular, the last 25-30 years have been by far the least war-afflicted in recent history, and have seen a correspondingly low number of casualties (Global Conflict Trends, 2014).

Why has the world become more peaceful? It may be partly due to the nuclear deterrent, the demise of Communist Bloc, increased international trade and commerce, the growth of democracy, the work of international peacekeeping forces, and increased interconnection between people of different nations. But sport is most likely an important factor too. It’s surely not a coincidence that, over the 75 years of this steady decline in conflict, sport has grown correspondingly in popularity. The excitement and intoxication which was once derived from warfare can be gained from from national and international sporting competitions, from following your country at the Olympics or the Soccer World Cup. The sense of belonging and allegiance to your army comrades or the sense of togetherness of being a nation at war can now be gained through supporting your baseball club. The heroism and loyalty or feeling of being “more alive” on the battlefield can be gained from the athletic or football field.

Race and Ethnicity Essential Reads

Why Black Celebrities Are Being Accused of “Selling Out”

The Black Wife Effect: How Relationships Shape Identity

This shows how essential it is for sport to be promoted in the world’s conflict zones. It shows how important it is for governments—and other organizations—to make sport more accessible and attractive to young people, particularly in areas of social deprivation, where gang membership flourishes. And it also shows that William James was right—war and conflict aren’t natural or inevitable, and can be transcended.