Two Years With No Moon

Immigration Detention of Children in Thailand

Rohingya women and children who arrived by boat from Burma pass the time at a closed shelter in Phang Nga, Thailand

Thailand: Migrant Children Locked Up

Thousands Held in Immigration Detention

Prologue: Bhavani and Her Sisters

From age 8 to 10, Bhavani spent two years locked up in Bangkok’s squalid, overcrowded Immigration Detention Center (IDC). She and her family, refugees from Sri Lanka, were detained because Thailand’s immigration laws precluded them from gaining legal status and protection in the country.

Bhavani is the youngest of six children. She was living in hiding in Bangkok with her mother, father, three sisters, and the younger of her two brothers. Early one morning when her mother and brother were out, the police raided the apartment, apprehended Bhavani, her father, and her sisters, and sent them to the Bangkok IDC. Her older brother had already been detained there for over a year, and even though they had not been able to see him—they lacked any paperwork that would let them visit—the family had some idea of the harsh conditions inside.

When Bhavani’s mother, Mathy, learned that her husband and daughters had been arrested, she was shocked. “I just thought I should surrender,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I wasn’t able to leave four of my girls in the IDC alone.” Mathy voluntarily reported to a court, where the judge ordered her to pay a 6,000 baht (about US$200) fine for being in the country without a visa, then let her surrender and join her daughters in the IDC. In the two days they were apart, Mathy said, “I felt like I was dreaming. I wasn’t able to sleep, I’d hear them talking like they were calling me, knocking at the door.”

When the sisters and their father reached the IDC—two days before Mathy arrived—the police separated the girls from their father and sent them to different holding cells. The girls were initially held in a large hall with many adults. “When they took our dad away from us, we started to cry. That’s when I realized we couldn’t get out of there,” said Amanthi, Bhavani’s sister, who was 12 at the time. “When I saw them there,” said Mathy, “I was so scared.”

After a few days, Mathy and her four daughters were moved to the cell where they would spend the next two years. The cell was overcrowded, sometimes with over 100 occupants. People were “sleeping all on top of each other, so crowded even right up to the toilet,” said Amanthi. “At some point we couldn’t sit.” Mathy said she coped as best she could, but “One of my sons was never arrested. It was really difficult. I wanted to be in the IDC with my girls, but I missed my second son.” He could not visit without risking arrest himself.

Because of the detention center’s policy of holding males in one cell and females in another, without chances to visit, the family was separated, despite being in the same facility. They were only brought together when a charity group visited once or twice per month and asked to see the whole family. “When Bhavani wanted to meet my dad or brother,” said Amanthi, “she’d really cry.”

Crammed in their cigarette smoke-filled, fetid permanent cell, the girls saw their health and education suffer. Bhavani developed a rash all over her body, but Mathy said the medication the IDC’s clinic gave her did not help. The toilets—just three for the hundred or so migrants held there—were filthy, and Bhavani’s teenage sister avoided using them because there were no doors. Though the International Organization for Migration ran a small daycare center that the girls could attend once or twice a week, there was no school. “I worried that my girls’ education stopped,” said Mathy.

Fights often broke out between women in the overcrowded cell, frustrated by their indefinite detention. “When someone behaved badly to other people, I didn’t like that,” said Bhavani. “They would shout at night.” The guards would not do very much when fighting started, and the girls would hide, explained Amanthi. “The [other migrants] are really, really strong. My mom didn’t know how to fight, she tried to take us to a corner and protect us. It was scary.”

Detained without release in sight, the family members slowly found ways to cope. “The first three to four months was really hard,” said Mathy. “It was difficult to manage and take care of my girls. I got used to it. We met people who had more problems than us.” Bhavani became friends with a Sri Lankan boy and girl detained with her. Their mothers would carve out a small space for them to play, defending the area against encroachment from others in the overcrowded cell.

Bhavani and her family were finally released on bail in the process of being resettled as refugees to the United States. Yet Bhavani, who had spent one fifth of her life in detention, had become accustomed to life in the IDC. When the family finally left, “I was so sad I had to leave my friends,” she said. “I knew they wouldn’t be coming out too.”

Now, living safely in the US, Bhavani has not seen her father in over a year. He was not cleared for resettlement alongside his wife and children, and, despite the risk of persecution, chose to return to Sri Lanka rather than remain in the IDC. The family decided that splitting up was the only way to get their children out of detention and back to regular education. Mathy still worries about the 20 or so other children left behind in her cell in the IDC: “Their education, their health, their future is spoiled.”

Summary

Every year, Thailand arbitrarily detains thousands of children, from infants and toddlers and older, in squalid immigration facilities and police lock-ups. Around 100 children—primarily from countries that do not border Thailand—may be held for months or years. Thousands more children—from Thailand’s neighboring countries—spend less time in this abusive system because Thailand summarily deports them and their families to their home countries relatively quickly. For them, detention tends to last only days or weeks.

But no matter how long the period of detention, these facilities are no place for children.

Drawing on more than 100 interviews, including with 41 migrant children, documenting conditions for refugees and other migrants in Thailand, this report focuses on how the Thai government fails to uphold migrants’ rights, describing the needless suffering and permanent harm that children experience in immigration detention. It examines the abusive conditions children endure in detention centers, particularly in the Bangkok Immigration Detention Center (IDC), one of the most heavily used facilities in Thailand.

This report shows that Thailand indefinitely detains children due to their own immigration status or that of their parents. Thailand’s use of immigration detention violates children’s rights, immediately risks their health and wellbeing, and imperils their development. Wretched conditions place children in filthy, overcrowded cells without adequate nutrition, education, or exercise space. Prolonged detention deprives children of the capacity to mentally and physically grow and thrive.

In 2013, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the body of independent experts charged with interpreting the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Thailand is party, directed governments to “expeditiously and completely cease the detention of children on the basis of their immigration status,” asserting that such detention is never in the child’s best interest.

***

Immigration detention in Thailand violates the rights of both adults and children. Migrants are often detained indefinitely; they lack reliable mechanisms to appeal their deprivation of liberty; and information about the duration of their detention is often not released to members of their family. Such indefinite detention without recourse to judicial review amounts to arbitrary detention prohibited under international law.

Thailand requires many of those detained to pay their own costs of repatriation and leaves them to languish indefinitely in what are effectively debtors’ prisons until those payments can be made. Refugee families face the unimaginable choice of remaining locked up indefinitely with their children, waiting for the slim chance of resettlement in a third country, or paying for their own return to a country where they fear persecution. Many refugees spend years in detention.

Immigration detention, particularly when arbitrary or indefinite, can be brutal for even resilient adults. But the potential mental and physical damage to children, who are still growing, is particularly great.

Immigration detention negatively impacts children’s mental health by exacerbating previous traumas (such as those experienced by children fleeing repression in their home country) and contributing to lasting depression and anxiety. Without adequate education or stimulation, children’s social and intellectual development is stymied. None of the children Human Rights Watch interviewed in Thailand received a formal education in detention. Cindy Y., for example, was three years older than her classmates in school when she was finally released. She said, “I feel ashamed that I’m the oldest and studying with the younger ones.”

Detention also imperils children’s physical health. Children held in Thailand’s immigration detention facilities rarely get the nutrition or physical exercise they need. Children are crammed into packed cells, with limited or no access to space for recreation. Doug Y. wanted to play football, his favorite sport, but said, “If you kick a ball, you’d hit someone, or a little kid.” Parents described having to pay exorbitant prices for supplemental food smuggled from outside sources to try to provide for their children’s nutritional needs. Labaan T., a Somali refugee detained with his 3-year-old son, said, “The diet for the boy consists of the same rice that everybody else eats. He needs fruits which are neither provided nor available for purchase.”

The bare and brutal existence for children in detention is exacerbated by the squalid conditions. Leander P., an adult American who was detained in the Bangkok IDC, said that one of the two available toilets in his cell, occupied by around 80 people, was permanently clogged, so “someone had drilled a hole in the side – what would have gone down just drained onto the floor.” Multiple children we interviewed described cells so crowded they had to sleep sitting up.

Even where children have room to lie down and sleep, they routinely reported sleeping on tile or wood floors, without mattresses or blankets. “The floor was made from wood, the wood was broken and the water came in,” said one refugee woman detained for months in the Chiang Mai IDC with a friend and the friend’s 6 and 8 year-olds. “While I was sleeping, a rat bit my face.”

Severe overcrowding appears to be a chronic problem in many of Thailand’s immigration detention centers. The Thai government detained hundreds of ethnic Rohingya refugees, including unaccompanied children, in the Phang Nga IDC in 2013. Television footage showed nearly 300 men and boys detained in two cells resembling large cages, each designed to hold only 15 men, with barely enough room to sit. Eight Rohingya men died from illness while detained in extreme heat with lack of medical care in the immigration detention centers that year.

Children are routinely held with unrelated adults in violation of international law, where they are exposed to violence between those detained and from guards. A Sri Lankan refugee, Arpana B., was pregnant and detained in an overcrowded cell in the Bangkok IDC with her small daughter in 2011. “One of the detainees beat my daughter,” she said. “He was crazy. There was no guard, no police to help us.”

Thailand faces numerous migration challenges posed by its geographical location and relative wealth, and is entitled to control its borders. But it should do so in a way that upholds basic human rights, including the right to freedom from arbitrary detention, the right to family unity, and international minimum standards for conditions of detention. Instead, Thailand’s current policies violate its international legal obligations, put children at unnecessary risk, and ignore widely held medical opinion about the detrimental effect that detention can have on the still-developing bodies and minds of children.

Alternatives to detention exist and are used effectively in other countries, such as open reception centers and conditional release programs. Such programs are a cheaper option, respect children’s rights, and protect their future. The Philippines, for instance, operates a conditional release system through which refugees and other vulnerable migrants are issued with documentation and required to register periodically.

Children should not be forced to lose parts of their childhood in immigration detention. Given the serious risks of permanent harm from depriving children of liberty, Thailand should immediately cease detention of children for reasons of their immigration status.

Key Recommendations to the Thai Government

- Enact legislation and policies to expeditiously end immigration detention of children consistent with the recommendations of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child.

- Adopt alternatives to detention, including supervised release and open centers that fulfill the best interests of the child and allow children to remain with their family members or guardians in non-custodial, community-based settings while their immigration status is being resolved.

- Until children are no longer detained, ensure that their detention is neither arbitrary nor indefinite, and that they and their families are able to challenge their detention in a timely manner.

- Drastically improve conditions in Immigration Detention Centers and any other facilities that hold migrant children in line with international standards, including by providing access to adequate education and health care and maintaining family unity.

- Sign and ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

Methodology

This report builds on two previous Human Rights Watch reports that examined Thailand’s treatment of migrants: Ad Hoc and Inadequate: Thailand’s Treatment of Refugees and Asylum Seekers (2012), and From the Tiger to the Crocodile: Abuse of Migrant Workers in Thailand (2010).

The report is based on 105 interviews conducted between June and October 2013, of people detained, arrested, or otherwise affected by interactions with police and immigration officials in Thailand. This report also uses an additional nine interviews, collected between September 2008 and October 2011 in the course of researching previous reports that refer to issues still relevant today. Interviewees ranged in age from 6 to 48, plus a grandmother who did not know her age. Fifty-five of the migrants interviewed were female. The majority of migrants interviewed were Burmese (including Rohingya); the next largest source country was Cambodia; and the remainder were from China, Nepal, Pakistan, Somalia, Sri Lanka, and the United States.

Forty-one of the interviewees were migrant children under the age of 18. Five others were adults under the age of 23 at the time of their interview who related experiences that occurred when they were children. We interviewed 10 adults who were parents of, related to, or had spent significant time detained with children below the age of 5.

We conducted some interviews in English and in Urdu, and others through the use of interpreters in a language in which the interviewee was comfortable, such as Rohingya, Burmese, Thai, or Khmer. We explained to all interviewees the nature of our research and our intentions concerning the information gathered, and we obtained oral consent from each interviewee.

Most interviews took place in Thailand, including in Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Mae Sot, Phang Nga, Ranong, and Samut Sakhon. We also interviewed, in their home country or in a third country, nine migrants and refugees who had been detained in Thailand. Most of these interviews took place in person; one took place by videoconference.

Most interviews were conducted individually and privately; this included extensive, detailed conversations with released detainees. In addition, Human Rights Watch researchers visited several immigration detention facilities and conducted group interviews with two or three of those detained at a time. In order to safeguard interviewees who were detained, our conversations took place outside the hearing of immigration staff.

Human Rights Watch researchers met eight government officials concerned with migration who worked for the police, immigration department, and the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. We also sent letters requesting data and other information concerning immigration and detention in Thailand, on January 18, 2014, to the Office of the Prime Minister, the Immigration Division, the Minister of Social Development and Human Security, and the Thai ambassadors to the United States and to the United Nations in Geneva and in New York. Although we received a letter from the office of the ambassador to the UN in Geneva acknowledging receipt of our letter, the office did not provide any answers to the questions we raised. We also sent a summary of our findings, and requested comment on July 15, 2014, to the ministries of foreign affairs and interior, and the Thailand mission to the United Nations in New York. The mission responded on August 14, 2014, and both our letter and their response are included as an annex to this report.

In addition, we met with representatives of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), officials of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), migrant community leaders, journalists, human rights lawyers, and activists.

All names of migrants interviewed, including those of all children, have been replaced by pseudonyms to protect their identity. Pseudonyms used may not match the country of origin. In cases where the interviewee was concerned about the possibility of reprisal, we have concealed the location of the interview or withheld precise details of the migrant’s case. Many staff members of government agencies, intergovernmental organizations, and NGOs in Thailand are not identified at their request.

Human Rights Watch did not assess whether the migrants we spoke to qualified for refugee status. Some, perhaps many, do. This report instead focuses on how the Thai government fails to uphold migrants’ human rights, regardless of whether or not those migrants have legitimate asylum claims or other protection needs.

On May 22, 2014, the Thai military took control of the government. Although the research for this report was completed prior to the coup, its findings remain relevant. The military government, known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), has instituted no major policy changes regarding detention of migrant children. Thailand’s policy of detaining migrants has remained consistent across previous governments, including military governments.

Terminology

This report focuses on migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in urban centers in Thailand. Most non-Burmese asylum seekers lodge refugee claims directly with UNHCR because Thailand is not party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (the 1951 Refugee Convention) and its 1967 Protocol, has no procedure for determining refugee status for urban asylum seekers, and has made no commitment to provide permanent asylum. UNHCR recognizes some as refugees but has no authority to grant asylum. The Thai authorities do not allow UNHCR to conduct refugee status determinations for members of certain nationalities, including Burmese, Lao Hmong, and North Koreans.

An “asylum seeker” is a person who is trying to be recognized as a refugee or to establish a claim for protection on other grounds. Where we are confident that a person is seeking protection we will refer to that person as an asylum seeker. A “refugee,” as defined in the Refugee Convention, is a person with a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” who is outside their country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return. In this report, we use the term “refugee” when that person has been recognized as a refugee by UNHCR in Thailand, though it should be noted that UNHCR recognition of refugee status is declaratory, which means that people are, in fact, refugees before they have been officially recognized as such.

In this report, “migrant” is a broad term used to describe foreign nationals in Thailand, including people traveling in and through Thailand and passengers on boats moving irregularly. The use of the term “migrant” does not exclude the possibility that a person may be an asylum seeker or refugee.

In line with international law, the term “child” as used in this report refers to a person under the age of 18,[1] including children traveling with their families and unaccompanied migrant children. This report discusses these groups separately and together, and uses the term “migrant children” to refer to them together. This term includes children who are seeking asylum or have been granted refugee certificates from UNHCR.

For the purposes of this report, we use the definition of “unaccompanied migrant child” from the term “unaccompanied child” employed by the Committee on the Rights of the Child: “Unaccompanied children” are children, as defined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, “who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.”[2]

I. Paths to Immigration Detention

There are approximately 375,000 migrant children in Thailand, including children who work, children of migrant workers, and refugee and asylum-seeking children.[3] Children constitute around 11 percent of Thailand’s total migrant population of 3.4 million people.[4]

Under Thai law, all migrants with irregular immigration status, even children, can be arrested and detained.[5] Immigration authorities and police arrest migrants while they are working, at markets, or as they travel within the country or seek to cross borders.[6]

Migrants of all nationalities who are arrested—and as a practical matter unable to pay bribes—are likely to be taken to police lock-ups or Immigration Detention Centers (IDCs). [7]

Those from countries bordering Thailand tend to spend a few days or weeks in detention before they are taken to the border to be deported or otherwise released. Nationals from countries that do not border Thailand, however, can spend years in indefinite detention, being essentially held until they can pay for their own removal.[8] Refugees can be held until they are resettled to a third country, an unlikely outcome for many refugees; and the relatively few who are resettled often spend many months, sometimes years, in detention prior to their resettlement.

Arrests of Migrant Workers and their Children

Thousands of migrant workers cross into Thailand each year from the neighboring countries of Burma, Cambodia, and Laos. Particularly those who remain unregistered with the Thai government face constant risk of arrest. These migrant workers make up a significant proportion of the workforce in Thailand.[9]Some bring children with them, and some give birth to children in Thailand. Infants stay in the migrant workers’ camps or in other homes with relatives, and young children attend informal schools in migrant communities. Many migrant children start working around 13, 14, or 15 years old.

Prior to the military coup of 2014, Thailand had made some progress toward regularizing migrant workers, but the process of applying for and gaining migrant worker status remained prohibitively expensive for many workers.

After the military coup, large numbers of Cambodian migrant workers left Thailand in response to rumors of migrants being arrested and harassed.[10] In just 18 days between June 8 and 25, at least 246,000 Cambodians fled the country, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM).[11] Cambodians in particular fear reprisals because of political tension between the two countries.[12] However, it is possible that Burmese and other migrants are also being targeted, but are less likely to flee due to conditions in their home countries.[13] The NCPO government denied that a crackdown on migrants is taking place and categorically denied all allegations of attacks and human rights violations against migrants.[14] On June 25, 2014, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) announced the creation of service centers to issue temporary entry permits to migrant workers and temporary work permits to their employers, both of which are required to obtain legal migrant worker status. After 60 days workers will have to verify their nationality before receiving a longer work permit. The announcement states that “relevant law enforcement entities shall strictly enforce the law” against migrants whose permits expire.[15]

Thailand routinely arrests migrant workers and their accompanying family members. Migrants, including children, report being arrested repeatedly. Nhean P., a 12-year-old Cambodian boy, said he had been arrested, detained, and deported three times in the past five years. He described his most recent arrest, in early 2012:

I was on the bus [with my mother and brother]. Police came and asked for ID – we didn’t have it. So they told us to get down and they took us to jail and sent us back to Cambodia. They sent us back in a pickup truck, without covering, open to the rain. We came right back to Thailand. [If we stayed] in Cambodia, we wouldn’t have any money.[16]

The lack of a legal framework in Thailand that recognizes and provides government-issued documents for refugees, and some obstacles to regularization for migrant workers, means that hundreds of thousands of Burmese adults and children are vulnerable to arrest on the street, workplace, or home. In most cases this can lead to detention and deportation.[17]

Police or immigration authorities raid migrant worker camps, other accommodation, or places of employment; they also stop migrants on the street or in markets. Aung M. was 13 years old in March 2013 when she went to a market in the town of Samut Sakhon with her two sisters. The police stopped them, arrested Aung, and took her to the police station as she had no papers. “I wanted to cry because I was afraid,” she said.[18] Her sisters, who had work permits, ran home and told her mother. Aung’s mother told Human Rights Watch, “The moment I knew, I was terrified. I had to find my daughter; I worried [that she would be deported to Burma]”.[19]

Parents reported fear of letting children leave their sight, in case they should be arrested. Phoe Zaw, a Burmese man in Mae Sot with a 12-year-old daughter, said, “I worry about my daughter. I’m afraid of the police. If she goes out and doesn’t come in on time, I go after her.”[20]

Police and immigration authorities frequently demand money or valuables from detained migrants or their relatives in exchange for their release, either from detention or at the time of arrest. Migrants reported paying bribes ranging from 200 to 8000 baht (US$6 to 250) or more, depending on the region, the circumstances of the arrest, and the attitudes of the officers involved. In some cases the migrant could be forced to pay the equivalent of one to several months’ pay in one incident.[21] The police sometimes tell apprehended migrants that they can pay a smaller amount directly to the police to avoid the higher fines they would be required to pay if taken to court.[22]

Sometimes children with a school ID card or in a school uniform are not arrested. (Thailand revised its education policies in 2005 in line with the “Education for All” movement principles to permit migrant children to attend Thai government schools.)[23] Koy Mala, a 13-year-old Burmese girl who attended government school, said, “My parents say that if the police come, wear your school uniform so they won’t arrest you.” She saw her 14-year-old classmate arrested by the police in 2013 when she was not wearing her uniform.[24]

Police arrest criteria seem arbitrary and vary considerably. Saw Lei, a Burmese man with migrant worker status who was living in Samut Sakhon, told us that in 2012 the police tried to arrest his then 10-year-old son, but when they discovered his son was a student at an unofficial migrant school, they let him go without requiring uniform or ID.[25] Yet Saw Lei’s daughter, who was 13 years old at the time, was arrested in a separate incident in 2012, even though she also went to the migrant school. She was released when her teacher came to the police station and vouched that she was a student.[26]

While Thailand has made progress in enrolling migrant children in school, there are still significant gaps, leaving some children vulnerable to arrest. “Many families live far into the fields,” said Saw Kweh, a veteran community activist in Mae Sot, “and schools can’t come pick them up. There are costs for going to school and some families can’t afford it.”[27]

“An Open Prison without End”

Myanmar’s Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State

A Myanmar police officer patrols the Thet Kae Pyin camp in Sittwe township where Rohingya Muslims have been confined since 2012, Rakhine State, Myanmar, September 7, 2016. © 2016 Kyaw Kyaw/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Summary

Myanmar: Mass Detention of Rohingya in Squalid Camps

August 24, 2020 News Release

Myanmar: Rohingya Await Justice, Safe Return 3 Years On

We have nothing called freedom.

–Mohammed Siddiq, lived in Sin Tet Maw camp in Pauktaw, September 2020

Hamida Begum was born in Kyaukpyu, a coastal town in Myanmar’s western Rakhine State, in a neighborhood where Rohingya Muslims, Kaman Muslims, and Rakhine Buddhists once lived together. Now, at age 50, she recalls the relative freedom of her childhood: “Forty years ago, there were no restrictions in my village. But after 1982, the Myanmar authorities started giving us new [identity] cards and began imposing so many restrictions.”

In 1982, Myanmar’s then-military government adopted a new Citizenship Law, effectively denying Rohingya citizenship and rendering them stateless. Their identity cards were collected and declared invalid, replaced by a succession of increasingly restrictive and regulated IDs.

Hamida found growing discrimination in her ward of Paik Seik, where she had begun working as an assistant for local fishermen. It was during those years a book was published in Myanmar, Fear of Extinction of the Race, cautioning the country’s Buddhist majority to keep their distance from Muslims and boycott their shops. “If we are not careful,” the anonymous author wrote, “it is certain that the whole country will be swallowed by the Muslim kalars,” using a racist term for Muslims.

This anti-Muslim narrative would find a resurgence years later. “The earth will not swallow a race to extinction but another race will,” became the motto of the Ministry of Immigration and Population. By 2012, a targeted campaign of hate and dehumanization against the Rohingya, led by Buddhist nationalists and stoked by the military, was underway across Rakhine State, laying the groundwork for the deadly violence that would erupt in June that year.

Hamida’s ward was spared the first wave of violence, but tensions grew over the months that followed. Pamphlets were distributed calling for the Rohingya to be forced out of Myanmar. Local Rakhine officials held meetings discussing how to drive Muslims from the town.

In late October 2012, violence returned. Mobs of ethnic Rakhine descended on the local Rohingya and Kaman with machetes, spears, and petroleum bombs. In Hamida’s ward, Rakhine villagers, often alongside police and soldiers, burned Muslim homes, destroyed mosques, and looted property. “The Buddhist people started attacking us and our houses,” Hamida recalls. “When we Muslims tried to protest and stand against the mob, the Myanmar security forces opened fire on us.” Soldiers shot at Rohingya and Kaman villagers gathered near a mosque, killing 10, including a child.

Hamida and her Muslim neighbors attempted to flee to Bangladesh. They arranged boats and set off at night. “We were on the Bay of Bengal for three days without any food,” she says. “When we arrived at the Bangladesh sea border, the authorities there provided us with some dry food—then pushed us back toward Myanmar.”

Hearing they could receive much needed food and aid at the camps in Sittwe, the Rakhine State capital, Hamida and her family made their way to Thet Kae Pyin camp. She lived there for six years with her husband and six children, first in a temporary settlement, later a shared longhouse shelter. Life in the camps brought hopelessness, fear, and pain.

“There is no future there,” Hamida says. “Do you think only tube wells and shelters inside the camp is enough to live our lives? We couldn’t go to market to get the items we needed, couldn’t eat properly, couldn’t move freely anywhere. We were in turmoil 24 hours a day.”

They were not allowed to study, work, or leave the camp confines. Hamida was unable to get the health care she needed.

“When our children died from lack of medical treatment, we had to bury them without any funeral,” she says.

In 2018, two of Hamida’s sons who had escaped to Malaysia spent 1,400,000 kyat (US$960) to send her and two of her daughters to Bangladesh. She sought medical care and the basic freedoms that her family had been denied for years. She now lives in another camp among nearly one million Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar. Her husband and two other children remain in Thet Kae Pyin, their requests to return home denied. She hopes one day they can all live in Kyaukpyu again. But only if they will be safe and free:

We want justice. We want to get back to our land. I have a desire to go back to my birthplace in Kyaukpyu before I die; otherwise, it’s better to die here in Bangladesh. Even the animals like dogs, foxes, or other creatures in the forest have their own land, but we Rohingya don’t have any place—although we had our own place once.

* * *

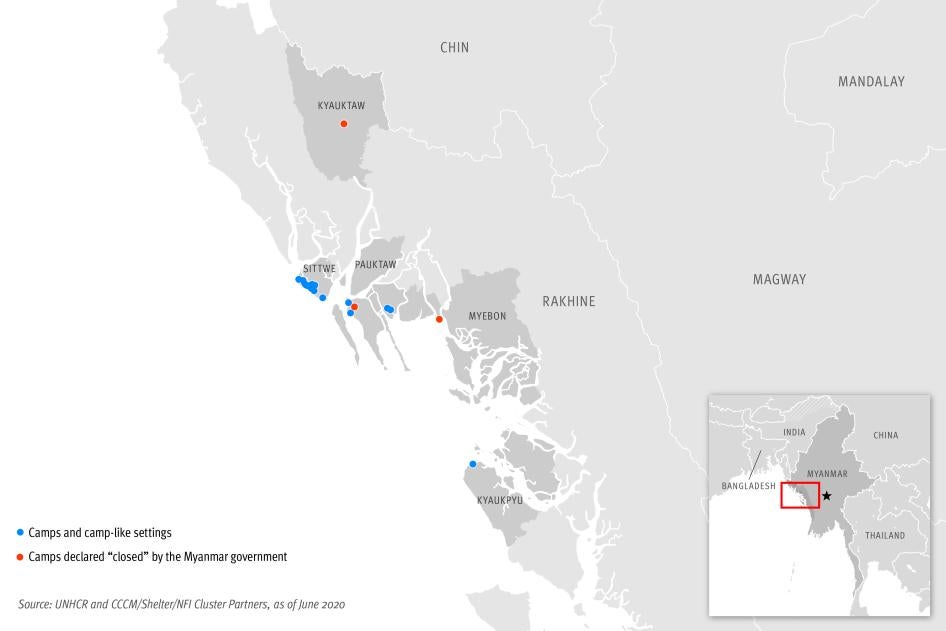

The 2012 coordinated attacks on Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State by ethnic Rakhine, local officials, and state security forces ultimately displaced over 140,000 people. More than 130,000 Muslims—mostly Rohingya, as well as a few thousand Kaman—remain confined in camps in central Rakhine State that are effectively open-air detention facilities, where they are held arbitrarily and indefinitely.

Many Rohingya told Human Rights Watch that their lives in the camps are like living under house arrest every day. They are denied freedom of movement, dignity, and access to employment and education, without adequate provision of food, water, health care, or sanitation.

The Myanmar government’s system of discriminatory laws and policies that render the Rohingya in Rakhine State a permanent underclass because of their ethnicity and religion amounts to apartheid in violation of international law. The officials responsible for their situation should be appropriately prosecuted for the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.

The 2012 attacks on the Rohingya ushered in an era of increased oppression that laid the groundwork for more brutal and organized military crackdowns in 2016 and 2017. In August 2017, following attacks by an ethnic Rohingya armed group, security forces launched a campaign of mass atrocities, including killings, rape, and widespread arson, against Rohingya in northern Rakhine State that forced more than 700,000 to flee across the border into Bangladesh. While these atrocities, which amount to crimes against humanity and possibly genocide, have drawn international attention, the Rohingya who remain in Rakhine State, effectively detained under conditions of apartheid, have been largely ignored.

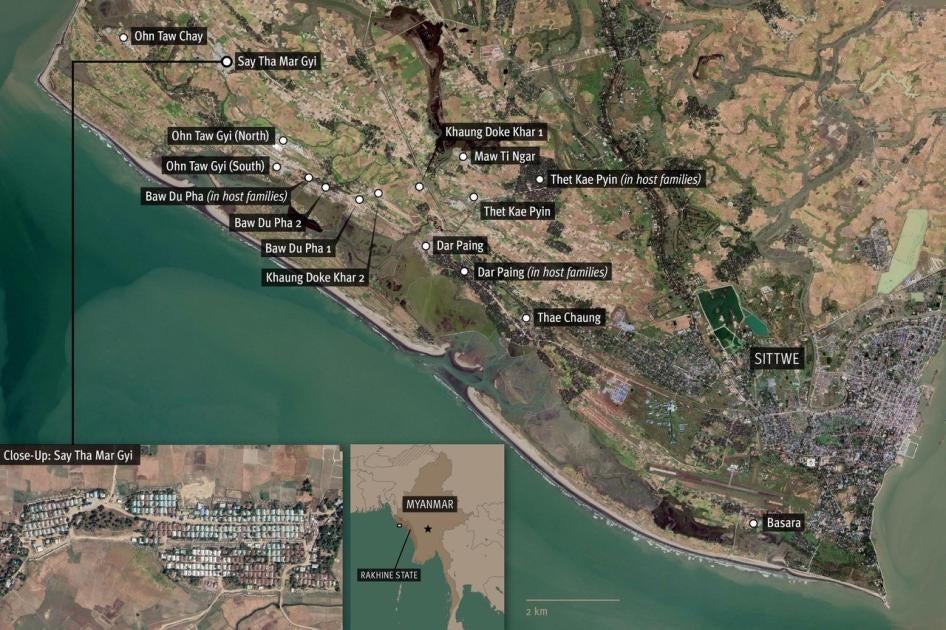

After the 2012 violence, the Rakhine State government segregated the displaced Muslims and ethnic Rakhine in Sittwe township in an ostensible effort to defuse tensions. While the displaced ethnic Rakhine have since returned to their homes or resettled, the government has maintained the Rohingya’s confinement and segregation for eight years.

Myanmar has failed to articulate any legitimate rationale for this extensive, unlawful internment. While the Rohingya have faced decades of systematic repression, discrimination, and violence under successive Myanmar governments, the 2012 violence provided a pretext for a longer term approach. “What they did in 2012 was overwhelm the Rohingya population,” said a UN officer who worked in Rakhine State at the time. “Corner them, fence them, confine the ‘enemy.’”

Rohingya in the camps are denied freedom of movement through overlapping systems of restrictions—formal policies and local orders, informal and ad hoc practices, checkpoints and barbed-wire fencing, and a widespread system of extortion that makes travel financially and logistically prohibitive.

Myanmar authorities meanwhile have enabled a culture of threats and violence that instills fear and self-imposed constraints. The central Rakhine camps violate international human rights law and contravene international standards on the treatment of internally displaced persons (IDPs), which provide that displaced populations “shall not be interned in or confined to a camp.” These violations are so severe that these camps cannot accurately be considered IDP camps at all, but rather open-air detention camps.

Access to and from the camps and movement within are heavily controlled by military and police checkpoints. Rohingya are not allowed to leave the camps without official, mostly unobtainable, permission. In the city of Sittwe, where about 75,000 Rohingya lived before 2012, only 4,000 remain. Surrounded by barbed wire, checkpoints, and armed police guards, they now live under effective lockdown in the last Muslim ghetto of Aung Mingalar.

The restrictions have given rise to a widespread system of bribes and extortion, while unauthorized attempts to leave result in arrest and ill-treatment. The constraints have tightened over the years. Mohammed Yunus lived in Ohn Taw Gyi camp in Sittwe before fleeing to Bangladesh. “During my years inside the camp, I saw the situation becoming more and more strict,” he said. “It was like an open prison without end.”

Myanmar officials have often invoked tensions between ethnic Rakhine and Muslim communities as the rationale for limiting Rohingya’s freedom to travel outside the camps. This claim is belied by the authorities’ involvement in stoking mistrust and fear and longstanding ability, demonstrated over decades of military dictatorship, to keep communal tensions in check.

The security risks posed at various points by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), the ethnic Rohingya armed group, and the Arakan Army, an ethnic Rakhine armed group, also fail to justify the repressive measures. The broad-based and harsh security restrictions imposed on Rohingya are unlawfully discriminatory, indefinite, and do not reflect specific security threats as international law requires.

The government’s policies have exacerbated the underlying ethnic tensions by failing to address hate speech and Buddhist nationalism, hold accountable perpetrators of violence, or promote tolerance. Instead of undertaking effective action to protect vulnerable communities, government officials have echoed and endorsed the threats, discrimination, and violence against the Muslim population.

A Rohingya woman from Aung Mingalar described her frustration with the government’s pretense: “They say, ‘Because of your security you can’t go outside [the camps].’ What security? If they wanted to put people in prison, they could. If they wanted to control the situation now, they could.”

Living conditions in the 24 camps and camp-like settings are squalid, described in 2018 as “beyond the dignity of any people” by then-United Nations Assistant Secretary-General Ursula Mueller. Severe limitations on access to livelihoods, education, health care, and adequate food or shelter have been compounded by increasing government constraints on humanitarian aid, which Rohingya are dependent on for survival. Fighting between the Myanmar military and Arakan Army since January 2019 has triggered new aid blockages across Rakhine State.

Camp shelters, originally built to last just two years, have deteriorated over eight monsoon seasons. The national and Rakhine State governments have refused to allocate adequate space or suitable land for the camps’ construction and maintenance, leading to pervasive overcrowding, high vulnerability to flood and fire, and uninhabitable conditions by humanitarian standards.

A UN official described her visit to the camps: “The first thing you notice when you reach the camps is the stomach-churning stench. Parts of the camps are literally cesspools. Shelters teeter on stilts above garbage and excrement. In one camp, the pond where people draw water from is separated by a low mud wall from the sewage.”

These conditions are a direct cause of increased morbidity and mortality in the camps. Rohingya face higher rates of malnutrition, waterborne illnesses, and child and maternal deaths than their Rakhine neighbors. An assessment of health data by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), a humanitarian organization working in the camps, found that tuberculosis rates are nine times higher in the camps than in the surrounding Rakhine villages.

Lack of access to emergency medical assistance, particularly in pregnancy-related cases, has led to preventable deaths. Only 7 percent of live births took place in health facilities during the first quarter of 2018, putting mothers and newborns in life-threatening risk. Child mortality rates are also high. During a 10-day period in January 2019, five children under 2 died from treatable diarrheal illness.

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the extreme vulnerability in which Rohingya live. They face threats from overcrowding, aid blockages, and movement restrictions that increase the risk of transmission, as well as harassment, extortion, and hate speech from authorities.

Rohingya children are denied their right to quality education without discrimination. About 70 percent of the 120,000 school-age Muslim children in central Rakhine camps and villages are out of school. Given the movement restrictions, most can only attend under-resourced temporary learning centers led by volunteer teachers. The only high school in central Rakhine State open to Muslims, located in the Sittwe camp area, has just 600 students and a 100:1 student-teacher ratio.

Rohingya have been barred from attending Sittwe University since 2012 for undefined “security” reasons. A Rohingya woman who passed the matriculation exam to study in Yangon in 2005 but was never granted permission to leave Rakhine said: “Since childhood, I have lost many opportunities for my education. If I could have come [to Yangon] in 2005, I could have changed my life.” In one camp, only 3 percent of women are literate.

This deprivation of education is a violation of the fundamental rights of the 65,000 children living in the camps. It serves as a tool of long-term marginalization and segregation of the Rohingya, cutting off younger generations from a future of self-reliance and dignity, as well as the ability to reintegrate into the broader community. It also feeds into the cycle of worsening conditions and services. Without opportunities for Rohingya to study to become teachers or healthcare workers, the community is left with a growing lack of trained service providers, particularly as ethnic Rakhine are often unwilling to work in the camps.

Restrictions that prevent Rohingya from working outside the camps have had serious economic consequences. Almost all Rohingya in the camps were forced to abandon their pre-2012 trades and occupations. Former teachers and shopkeepers have been left seeking ad hoc and inconsistent work as day laborers for an average of 3,000 kyat (US$2) a day. An 18-year-old from Say Tha Mar Gyi camp said: “Some of us want to run our own businesses but we don’t have money to invest. Some of us want to be carpenters but we don’t have tools. Some of us want to go fishing but we don’t have boats.”

The seeming unending joblessness is a significant push factor in Rohingya seeking high-risk avenues of escape from the camps. Since 2012, more than 100,000 have willingly faced the threat of drowning at sea or abuse by traffickers to seek protection and the chance for a new life and work in Malaysia and elsewhere. A Rohingya woman explained: “We know we will die in the sea. If we reach there, we will be lucky; if we die, it is okay because we have no future here.”

The National League for Democracy (NLD) government, under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi, has repeatedly demonstrated its unwillingness to improve conditions for Rohingya since taking office in 2016 following a half century of military rule. A Rohingya woman who fled Rakhine State described the lack of political will:

After the 2015 elections [when the NLD won], they have hope in the camps. They think things will change. After one year, they realize the Lady [Suu Kyi] will not do anything for us. They flee again. They are hopeless. She really doesn’t care. If the government wanted to control the monks, hate speech, it could.… Daw Suu is always talking about rule of law. If she actually practiced rule of law, we would be okay.

Little seems likely to change with the upcoming November elections. Most Rohingya have been barred from running for office and stripped of their right to vote.

Rohingya living in the camps have consistently expressed their desire to return to their homes, villages, and land, a right that the government has long denied. As Myo Myint Oo from Nidin camp said: “We want to go back to our places of origin and work our jobs again and live again with our neighbors in peace, like before 2012. We want to live in a safe place with other people, permanently.”

No compensation or other form of reparation has been provided for lost lives, homes, or property. A Kaman Muslim community leader said: “Nobody has been able to return, nobody has been compensated. We keep asking, even still we are asking the government for our land.… The land is still empty, there are no buildings there. We are still asking.”

In response to recommendations in an interim report from the government-appointed Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, led by the late UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the government announced in April 2017 that it would begin closing the camps. Its approach, however, has entailed constructing permanent structures in the current camp locations, further entrenching segregation and denying the Rohingya the right to return to their land, reconstruct their homes, regain work, and reintegrate into Myanmar society, in violation of their fundamental rights.

As noted in a March 2019 memo by the UN-led Humanitarian Country Team:

The Humanitarian community recognizes that the activities undertaken by the Government thus far in the framework of its “camp closure” plan are contributing to the permanent segregation of Rohingya and Kaman IDPs, and have not provided any durable solutions for IDPs or improved their access to basic human rights.

In November 2019, the government adopted the “National Strategy on Resettlement of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and Closure of IDP Camps,” which it claimed would provide sustainable solutions. Yet the steps undertaken thus far offer no sign of improving the “closure” process or having any positive impact on the lives of camp detainees. A UN official called the strategy development “just a smokescreen,” and a 2020 UN analysis concluded: “The implementation of the strategy, in of itself, will unlikely resolve the fundamental issues that led to the displacement crisis in Rakhine state.”

The camp “closures” being carried out fall far short of the safe and dignified solution to displacement called for under international standards. Rohingya and Kaman as well as humanitarian agencies report that in the three camps labeled “closed,” there has been no notable increase in freedom of movement or access to basic services.

“Nothing has changed,” a Rohingya man living in one of the “closed” camps said. “We have had individual shelters since August 2018, but everything else has stayed the same. We don’t have freedom of movement, and still have major challenges for livelihood, income, and health.”

The camp closure process has triggered the UN and humanitarian groups to reevaluate their approach to working in the camps. These agencies have a humanitarian mandate to assist wherever it is needed, and the needs of the Rohingya in the camps are vast. But working in the camps for eight years has increasingly threatened to make them complicit in what agency staff have determined to be a government effort at permanent segregation and deprivation. Many are questioning their engagement with a government and military that have threatened and manipulated their operations for years.

One UN officer said: “Do you really want to invest millions in making concentration camps better? That is the question we’re facing.… You are helping them become permanent detainees.”

An internal UN discussion note from September 2018 asserted that despite the humanitarian community’s efforts, “the only scenario that is unfolding before our eyes is the implementation of a policy of apartheid with the permanent segregation of all Muslims, the vast majority of whom are stateless Rohingya, in central Rakhine.”

After eight years of de facto detention, the sense of hopelessness among displaced Rohingya is pervasive, and only worsened by the meaningless assurances of camp closures. Not one Rohingya interviewed by Human Rights Watch expressed a belief that their situation in the camps could improve, that their indefinite detention may end, or that their children could one day live, learn, and move freely. “How can we hope for the future?” said Ali Khan, who lives in a camp in Kyauktaw. “The local authorities could help us if they wanted things to improve, but they only neglect [us].”

“I think they won’t solve this problem,” a Rohingya woman who had escaped Rakhine State said of the government’s plan to close the camps. “I think the system is permanent. A long time ago they took our money. Nothing will change. It is only words.”

In September 2012, then-UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar Tomás Ojea Quintana gave a prescient warning about the government’s plan:

The current separation of Muslim and Buddhist communities following the violence should not be maintained in the long term. In rebuilding towns and villages, Government authorities should pay equal attention to rebuilding trust and respect between communities.… A policy of integration, rather than separation and segregation, should be developed at the local and national levels as a priority.

Yet, rather than “rebuilding trust and respect,” the government has maintained the Rohingya’s confinement and segregation for eight years—while having since resettled or returned the thousands of displaced Rakhine Buddhists—exacerbating ethnic and religious discrimination with devastating impact.

The 1973 Apartheid Convention applies to “inhumane acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” Apartheid and persecution are also crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

As the term “racial group” has been defined under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racism (ICERD) and by ad hoc international criminal tribunals, the Rohingya, as an ethnic and religious group, should be considered a distinct racial group for purposes of the Apartheid Convention.

Myanmar government laws and policies on the Rohingya community, notably their long-term and indefinite confinement in camps and villages, and regime of restrictions on movement, citizenship, employment, housing, health care, and other fundamental rights, demonstrate an intent to maintain domination over them. The adoption of many of these practices into state regulations and official policies and their enforcement by state security forces shows an intent for this oppression to be systematic.

Specific inhumane acts applicable to the government’s apartheid system include denial of the right to liberty; infringement of freedom or dignity causing serious bodily or mental harm; and illegal imprisonment. Various governmental measures appear calculated to prevent members of the Rohingya population from participating in the political, social, and economic life of the country, and deny group members their rights to work, to education, to leave and to return to their country, to a nationality, and to freedom of movement and residence. The government has also imposed measures designed to divide the population along racial lines by the “creation of separate reserves and ghettos” for the Rohingya and the confiscation of property.

All of these acts are ongoing in Rakhine State and amount to a regime of apartheid against the Rohingya.