Kim Gardner to face disciplinary panel Monday over claims stemming from Greitens probe

Law expert calls allegations ‘nonsense,’ while opponents say her actions were ‘gross prosecutorial misconduct’

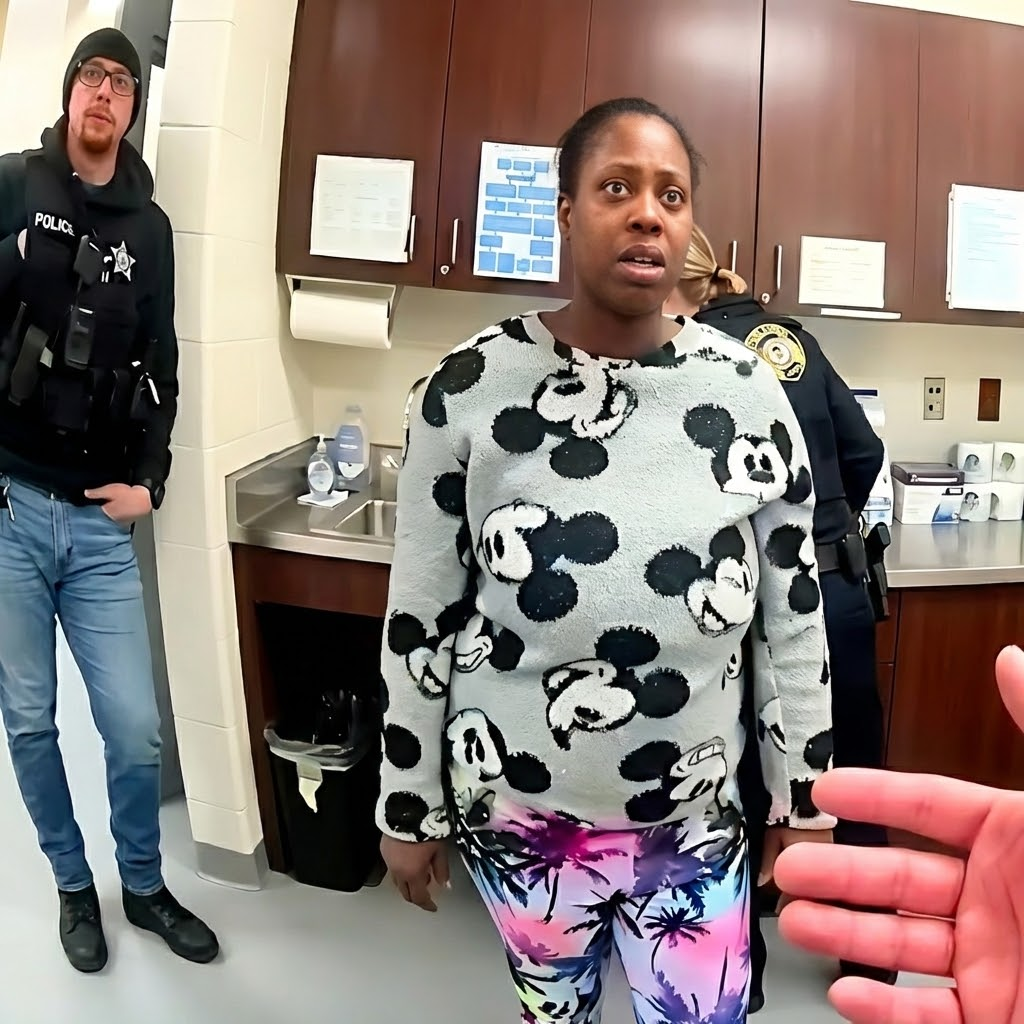

St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kimberly Gardner was surrounded by supporters on July 11, 2019 when she made public remarks following the lifting of a gag order regarding an investigation into her office’s handling of the Eric Greitens case (Wiley Price/St. Louis American).

Three years ago this month, a dozen police officers raided the office of St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner.

They were executing a search warrant connected to the ongoing investigation of William Tisaby, an ex-FBI agent Gardner had hired to assist her in the 2018 investigation of former Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens.

Tisaby would eventually plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge of evidence tampering.

But the saga continues for Gardner — and will culminate at 9 a.m. Monday, when Gardner will face a three-person panel with Missouri’s attorney disciplinary system.

The panel will be recommending to the Missouri Supreme Court if Gardner should lose her law license — and her job as prosecutor — or face other discipline as a result of alleged misconduct during the Greitens probe.

During Greitens’ trial, defense attorney James Martin called Gardner’s actions, “gross prosecutorial misconduct.” But Gardner contends the investigation is simply an attempt by opponents, largely outside of the city, to oust a progressive-minded prosecutor trying to reform the criminal justice system.

“If there were minor mistakes made, they were not deliberate, they did not undermine justice, and they did not deny the defendant a fair trial,” according to her written response to the claim.

Bennett Gershman, law professor at Pace University whose 1985 book “Prosecutorial Misconduct” has been referenced by scholars for decades, said the ethics complaint against Gardner is “nonsense.”

“It’s just a total train wreck,” Gershman said, after reading the filings in the ethics case. “Very little to do with the facts. Very little to do with law. Very little to do with ethics. Almost everything to do with politics.”

Gershman added that he nearly fell out of his chair when he read the details of the raid on Gardner’s office.

Officers allegedly threatened to kick in the door of the IT room, forced an employee to provide the passwords to her entire computer system, and then took the office’s entire server, according to a lawsuit Gardner filed in 2020.

On the server was information of about 40 investigations of alleged police misconduct, which contained “sensitive” information about the health and financial information of witnesses, subjects, and targets of grand jury investigations.

This kind of raid on a prosecutor’s office is “absolutely unheard of,” especially for a perjury investigation, Gershman said.

“If what Kim Gardner alleges is true, it is one of the most grotesque, extraordinary violations of a search warrant that I’ve seen,” said Gershman, who lives in New York and has never met Gardner.

The log

The 2019 raid produced a document with bullet points of Gardner’s thoughts, after interviewing a woman who had an extramarital affair with Greitens three years earlier.

The woman, who was referred to as K.S., alleged Greitens had threatened to release a nude photograph of her, taken against her will while she was blindfolded and her hands were bound, if she told anyone of a sexual affair.

The bullet points are now the focus of the ethics complaint.

On Jan. 24, 2018, Gardner met with K.S. at an Illinois hotel. At the meeting, Gardner started taking handwritten notes, but then the woman’s attorney asked her to stop. So instead, Gardner just listened for the remainder of the time.

Over the next few days, Gardner typed up some of her thoughts on her iPad, including what she remembers K.S. saying during their meeting, but they weren’t direct quotes, she states in her response.

During the trial, Gardner’s team handed over the handwritten notes she took before she was asked to stop – knowing that this type of record is required by law to be given to the defense attorneys. But they didn’t hand over the iPad document with her thoughts, and Gershman said that’s common practice.

“Every lawyer is allowed to keep confidential the lawyer’s work product,” Gershman said, noting that he means lawyers’ recollections when interviewing witnesses. “It is enjoyed by every lawyer in the country, including prosecutors. And there is no case, that I know of, which holds that a lawyer is required to disclose their work product.”

Gardner said she didn’t know the document still existed until the raid turned it up, according to her response to the claims.

Chief Disciplinary Counsel Alan Pratzel alleges in a 73-page probable-cause document that her notes should have been added to a “privilege log” – or a list of documents that Gardner’s team believed weren’t required by law to be given to Greitens’ attorneys. The judge wanted to review the list to ensure the documents were privileged.

Gardner said the person in charge of compiling the privilege log for the judge was her chief trial assistant Robert Dierker, who had formerly been the presiding judge of the 22nd Circuit (where the Greitens case was being heard) and a judge for more than 30 years before joining her team. She took his advice on what to include on the log, she states in a response, and believed that Dierker and Greitens’ attorneys had agreed on what should be on the log.

Pratzel argues Gardner violated several rules when she and her team falsely stated that they had made all of their notes known to the judge and Greitens’ attorneys.

“It seems to me the gist of the ethics investigation and charges against Kim Gardner are that she failed to disclose something,” Gershman said. “But if she failed to disclose something that is not required to be disclosed, then what? What did she do that was improper or unethical?”

Tisaby’s notes

Gardner had emailed her bullet-point notes to Tisaby before he interviewed K.S. on Jan. 29, 2019 on video – a recording that was given to the defense.

Although Tisaby had told Gardner that he wasn’t going to use her notes, Tisaby had actually reformatted her words into a new document — cutting off the last several pages — and printed it, Gardner’s response states. Then during the interview, he took 11 pages of handwritten notes on top of that print out.

Tisaby’s reformatting of her thoughts are also central to the ethics complaint.

During the trial, Greitens’ defense team deposed Tisaby for nine hours, where he said that he didn’t take notes during that meeting. However, once the defense got a copy of the video, it showed Tisaby writing notes while speaking to K.S.

So Gardner’s team handed over Tisaby’s notes on April 11, 2018.

Pratzal alleges Gardner should have corrected the record when Tisaby failed to acknowledge in court that he received documentation from Gardner about the Greitens’ case before interviewing Greitens’ accuser – the basis of Tisaby’s misdemeanor plea.

However, Gardner responded that she was not acting as Tisaby’s attorney when those statements were made. At that point, Greitens’ defense team had succeeded in making Tisaby a witness in the case.

After receiving Tisaby’s notes, Greitens’ attorneys argued in court that Gardner was sitting next to Tisaby when he was writing so she knew the notes existed. They claimed that she concealed evidence, allowed Tisaby to give false statements under oath and asked the judge to sanction Gardner and dismiss the case.

A month later, Gardner dropped the invasion of privacy case against Greitens, after his defense prevailed in making Gardner a witness in the trial as well and Tisaby a potential defendant.

After Gardner bowed out of the invasion of privacy case, Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker took it over. It was eventually dropped, citing statutes of limitation that had or were about to pass and potentially missing evidence.

Last month, Greitens’ ex-wife filed an affidavit as part of a child custody dispute alleging he had been physically abusive to her and their children. She also claims Greitens admitted to her in late January 2021 that he had in fact taken the photo of K.S. that resulted in the invasion of privacy charge.

Gardner has repeatedly said the ethics complaint is not about prosecutorial misconduct.

“The Greitens team’s strategy ultimately proved largely successful: Mr. Greitens avoided a criminal conviction – and is now running for United States Senate – while Ms. Gardner faces this disciplinary proceeding that could result in unfair and unwarranted mistrust of the Circuit Attorney’s office,” her response states.

Ethics complaint process

On July 2, 2018, an ethics complaint was filed against Gardner in the Office of Chief Disciplinary Counsel regarding her conduct in the case, and Pratzel began his investigation.

On March 1, 2021, Pratzel formally started disciplinary proceedings by filing a probable cause document.

Whether or not Gardner has committed professional misconduct is now the question before a three-person panel, which includes two lawyers and one non-lawyer.

At the hearing beginning Monday, both sides are expected to present their evidence. After which, the panel will make a written determination and recommendation as to any discipline, which can range up to disbarment. It takes place at the St. Louis County Courthouse in Clayton.

However, this is likely not the end of the proceedings.

After the panel’s written decision, both parties have 30 days to accept or reject it. At that point, the panel’s decision and the parties’ responses will be filed with the Supreme Court. From there, the Supreme Court could make a decision based on the filings, or it could schedule the case to be briefed and argued.

Regardless, the ultimate decision regarding discipline lies with the state’s highest court.

When asked if he believes a recommendation for Gardner’s discipline could set a precedent in other such cases, Gershman said he doesn’t foresee it being replicated.

“Because I think this case is an aberration,” Gershman said. “And I underline the word ‘aberration.’ I’ve never seen anything like this.”

Philosophical and Legal Aspects of Human Rights

Theoretical Underpinnings of the Human Rights Concept Baroness O’Neill, President-elect British Academy; Principal, Newnham College, University of Cambridge, U.K.

To be handed the topic “The Theoretical Underpinnings of Human Rights” is to be handed rather a lot. I decided that the talk I should give would be a questioning talk, “putting the cat among the pigeons” as we say here. It is often said that practice is weak in the observation of human rights; the contrasting thought is that theory is strong and underpinnings are available. I agree that practice is weak, but I’m afraid that the underpinnings are also fragile. If we care about the things that human rights are intended to protect, we have some reason to think quite critically about the theoretical underpinnings. This is not meant in any way to be critical of efforts to protect the things that we take human rights to protect.

The ideology of human rights has become a dominant ideology. And we know what happens to dominant ideologies in the long run. That is why, if we have reasons to care about the things that human rights protect, we better think about why and how this ideology is vulnerable. I do not, of course, mean that it is well respected. In fact, I think it may get too much complacent lip service. But it may be in quite deep danger. The deep problem, in my view, is that human rights claims have not been well justified philosophically; they have not even been well defined. I’m going to illustrate some defects in justification by commenting on the historic emergence of the human rights culture, and I shall illustrate some defects and confusion of definition by brief comments on one right that matters to academics, which is freedom of the press or freedom to publish.

The first point I wish to make is that the idea of rights as the fundamental ethical category is a historical curiosity. It is very unusual to look at morality or politics or society, not from the point of view of agents, but of recipients, which is what the culture of human rights does and often commends itself for doing. I think it may be salutary to remember that, traditionally, the primary normative claims have been claims about human obligations or duties. That switch from talking about the duties of man to the rights of man was first made in the late 18th century.

It is not easy to establish what duties human beings have. If we could establish that, then we could show who ought to do what for whom and under what circumstances, and that is the important or practical thing. If we have duties, we can be clear also about who might benefit from their discharge and who might have a claim to their discharge. If we can’t establish anything about duties, then we’ll have only grief by making claims about rights. Duties, obligations, actions, are the business end of normative requirements, whether moral, legal, or professional. I’m arguing for obligations before rights.

Let’s think a bit about the structure of universal obligations. There are some—the duties that correspond to what we often call liberty rights—that are connected to first-generation rights, which are seen as universal duties owed by all agents to all agents. If we can justify them, that will be very good news. We may be able to, because we would thereby justify rights claims. If

we show there are universal duties not to deny others free speech, this would justify a universal right to speak freely, because that right could be claimed—one would know where to claim it.

The duties that correspond to supposed goods and services, often slightly inaccurately called welfare rights, are more difficult. Such duties, even if universal, cannot be owed by each to all. If you think about a right to food, for example, it cannot mean that each of us has an obligation to feed all others, but rather at most by each to some or some to some. These are duties that cannot be owed to all others and cannot be discharged to all others. Such duties have to be allocated to specified agents, who carry the duties. In this case, any counterpart rights that we’re hoping for are going to be undefined pending an allocation of duties until duties therewith some rights are institutionalized.

Historically the arguments about establishing duties have been of many sorts, and many within religious traditions. Some have been based on theories of the good for man. Some of those theories have been objective, Aristotle for example, some subjective, utilitarianism for example, and some pure theories of duties, Kant for example. But until the late 18th century, nobody argued that rights were the fundamental, normative issue. Actually, I’m not sure they argued the case—they proclaimed it.

There is much to be said for giving up on justification and going for proclamation. Bertrand Russell put it rather nicely, “The advantages,” he said “of the method of postulation are great—they are the same as the advantages of theft over an honest dollar.” That is to say, you get your conclusions without working for them.

Now, twice in human history, we have seen this shift to making rights discourse the prominent or a prominent public discourse, not by justification, but by proclamation. The first time was in the 18th century, in 1789, in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and it was criticized from very early on. Burke campaigned against it. Bentham famously wrote, “Right is a child of law,” (only positive rights). “From real laws come real rights, but from imaginary laws, from the ‘law of nature,’ come imaginary rights. Natural rights is simple nonsense; natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense – nonsense upon stilts.” John Stewart Mill argued that rights were a derivative notion. Positive rights were important precisely because they contributed to utility and human happiness.

Finally, 19th century historicists and legal positivists put the notion of human rights in such bad odor that it sank from human history. Proclamation, when you think about it, is a use of the argument from authority, and none of us as scientists and scholars would wish to take an unalloyed view of the argument from authority. Of course, it has a somewhat different status in limited context and in legal argument, which often explains quite a lot.

In the 20th century, there is a second attempt, with the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This was devised in an utterly different historical context—a need to find universal standards. There was great difficulty in agreeing on serious arguments for those standards and, therefore, certain rather general phrases were agreed to, the so-called “human rights,” to which some universal obligations were then alleged to correspond. Essentially it was a second version of proclamation. That declaration was codified in 1966. We have the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. In all these documents, and in many other international documents and regional documents like the European Convention on Human Rights, it is clear that the obligations are seen as secondary.

When you look closely, the covenants and other documents do not assign to the states obligations to meet rights, but second-order obligations to ensure that rights are secured and are met. That may be a very reasonable route. For example, in the Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, we read that each state party to the present covenant undertakes to take steps individually and through international assistance and cooperation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized or proclaimed in the present covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures. One might again think Bertrand Russell’s thought. In fact, some people, in the very era in which the Universal Declaration was drafted, did warn (prophetically, I think) that it was dangerous to be looking at the rights without looking at the obligations.

I cannot resist quoting to you the first sentence from a book that should be better known, by Simone Weil, a French philosopher who came as an exile to this country but died before the Second World War ended. Those two sentences read, “The notion of obligations come before that of rights, which is subordinate and relative to the former. A right is not effectual by itself, but only in relation to the obligation to which it corresponds, the effective exercise of a right springing not from the individual who possesses it, but from other men who consider themselves as being under a certain obligation towards him.”

Lawyers have a way of dealing with these issues about difficult underpinnings. Maybe we should take a tip from Jeremy Bentham and think about law and institutions sooner, rather than trying to treat proclamations as justifications. That is not going to make everybody happy, because many people want to think that human rights are pre-conventional and that law just comes along afterward to tidy up, recognize, institutionalize, and secure preexisting rights. There may nevertheless be something to be said for taking some of the arguments of the legal positivists seriously.

One view quite often found among international lawyers is the following. When human rights were first proclaimed in the declaration and the covenants, they indeed lacked authority. That was mere proclamation. But now, the relevant covenants have been signed and ratified by the states parties, so now they are binding. Now they are real obligations. Note, however, that there is a sting in the tail here. Signature and ratification will not establish universal rights, and human rights are meant to be universal rights. What signature and ratification will establish is a special obligation on those states that sign and ratify—hence not on all states, and it is not a universal obligation. Moreover, they establish a special obligation that is not the counterpart of any universal right, but an obligation to institutionalize certain positive rights—that obligation to achieve progressively the full realization, etc. We are not going to find a justification, theoretical underpinnings, down that route.

Let me give you one example that shows that we also suffer from poor definitions of rights. I’ve chosen press freedom, and one of the reasons why we are not so good at justification—we all take it for granted that it is important, that justification needs argument—is that we are relatively unclear about what exactly this freedom is, what right holders can claim, and what the obligation bearers ought to do and ought not to do. The unclarity, of course, has short-term advantages. Paper over the cracks and you get seeming agreement, but down the road you may get deep, radical dissension.

This freedom of the press matters to all of us as scholars and scientists, and, in the United Kingdom, we have a particularly lively debate because of certain features of our press, which many of you will be aware of. A character in a play by Tom Stoppard exclaims to another, “I’m with you on the free press; it’s the newspapers I can’t stand.” I think we could all sympathize with that thought. In fact, when you look at it, freedom of the press is so poorly defined that it is not clear to many people whether the newspapers that we can’t stand are acting within freedom of the press or violating it.

Some see freedom of the press as an unconditional right to publish just about anything, providing you don’t harm or injure an individual—libel, slander, clear and present endangering. There are four arguments in common use. One of them is the jurisprudential argument, which, in many ways, is the one I’ve already mentioned. One appeals to authority. One says, look, the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution says Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of the press. Or one appeals to Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Unfortunately, as noted, arguments from authority, effectively proclamations, don’t provide justifications. All press freedom can be defended, and it often has been defended by academics as the means for discovering truth. I think the earliest and probably most famous formulation of that argument was by John Milton in the 17th century in Areopagitica “Who ever knew truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?” Well, I’m not sure that is true. If you actually think about what it takes to get truth in your own discipline, it is not as if it were completely untrammeled self-expression. It is, as the late Bernard Williams pointed out in his book Truth and Truthfulness, “A matter of very careful communication that is regulated in very careful ways.” Williams wrote, “In institutions dedicated to finding out the truth, such as universities, research institutes and courts of law, speech is not at all unregulated. We have processes. We do not regulate content, and we do not forbid the utterance of content, but we have fierce procedures for finding the truth. The search for truth needs structures and discipline and is undermined by casual disregard of accuracy or evidence or process that permits casual disregard.” The needs of truth-seeking actually weren’t justified, unconditional press freedom.

A more contemporary way of going at it is to say press freedom is just a special case of freedom of expression—Article 19 of the Universal Declaration and Article 10 of the European Convention. Freedom of expression might be justifiable for individuals as an aspect of individual freedom. Kant called it the most innocuous freedom; Mill saw it as a merely self-regarding activity with which others shouldn’t interference. Could freedom of expression justify unconditional press freedom, particularly in an era in which the media have become powerful, as they were not in the 19th century? We don’t permit companies to invent their balance sheets on the grounds that they need freedom of expression. We don’t permit public authorities to be imaginative in their accounts and reports. Should we permit the press to be inaccurate? Can we

find arguments for allowing the powerful, unconditional freedom of expression not only to inform, but also to misinform and to disinform? I doubt we are going to get a good argument for freedom of expression for the powerful.

Appeals to democracy seem to me a better way to go with press freedom because democracy needs a press that informs citizens. But if requirements for accurate reporting were too tightly drawn, that would be intimidating for the press. Nobody can be sure of getting things right all the time—not even scientists and scholars. A press that serves rather than damages democracy needs to aim for accuracy, but it cannot be required to achieve it. We can require truthfulness but not truth. This standard can be met by providing evidence, by including caveats and qualifications, by prompt correction of error, by distinguishing reporting from commentary, rumor, gossip, and the like. These forms of epistemic responsibility allow our readers to judge for themselves, but they are not arguments for unconditional press freedom.

These four, or, if you dismiss the argument from authority, three arguments for press freedom are arguments for quite differing and carefully configured rights, which we can see only when we think what the counterpart obligations are. If we look at the obligations, we may also be able to reach some justifications.

In the end, I believe that if we care about the things that human rights are intended to protect, we ought to focus, not on the rights, but on the business end of the matter, which is the counterpart obligations. We ought to focus not only on the enactment of such obligations, on requiring them and reinforcing them by law, but also on the underlying arguments.

Think about what happened in the 19th century. Think about why rights disappeared from public discourse, and I think it is a salutary reminder. Thank you.

Discussion

Arnold Wolfendale, Academia Europaea – It seems to me the pendulum has swung a bit too far in the direction of promoting human rights, without at the same time promoting responsibility for those who are speaking about them. I was wondering whether the Network should be devoted not just to human rights, but to human rights and responsibilities. Our advice to presidents, kings, and others would be more appreciated if it were clear that we are interested in responsibilities as well as rights.

O’Neill – I was making a slightly different and rather stronger claim than the usual one about rights going with responsibilities. I think that claim is true. Most people who have rights, for example, each of us, also have responsibilities. But some people who have rights do not have responsibilities—for example, infants. I was making the stronger but more limited claim that nobody has a right unless somebody (usually somebody else and some other institution) has obligations. That is why I stuck to the obligation vocabulary and not to the rights and responsibilities, which I think is a much softer claim.

Should we be talking about obligations in our institutions? Yes, I believe so, and I believe if we are to carry the day in many institutional contexts, it is extremely important to talk